The death of Ken Barrington, aged just 50, during England’s tour of the West Indies in 1980-81 stunned cricket. His talent as a batsman was put into perspective by John Woodcock in the 1970 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack.

The illness which ended Ken Barrington’s career at the age of thirty-eight revealed the extent to which a rugged physique had been undermined by the anxieties of representative cricket. It also deprived England of a remarkable batsman.

Between 1959 and 1968 Barrington amassed runs, for Surrey and more particularly for England, with implacable intensity. It was his ambition to surpass every Test match aggregate, and he was well on the way to doing so when the effort caught up with him.

Playing in Melbourne, in a double-wicket tournament, he suffered a thrombosis which led to his announcing his retirement in April 1969. Now, as the father of a new-born son, a writer on the game, the co-owner of a sports clothing business and a keen golfer, he is leading a relaxed and happy life.

Barrington represented England in 82 Tests, averaging an astonishing 58.67 with the bat

Barrington represented England in 82 Tests, averaging an astonishing 58.67 with the bat

To say that Barrington had a unique appetite for runs would be to go too far. Bradman and Ponsford, Hutton and Hanif Mohammad, to mention only four, were no less insatiable. But as a percentage player I doubt whether there has ever been anyone to equal Barrington. He joined Surrey, from the Reading Club, in 1948, when he was 17. During National Service from 1949 to 1951 he was still looked upon mainly as a bowler. But on his return to Surrey it was as a batsman that he established himself in the county side.

By 1955 he was making enough runs to be chosen for England against South Africa. In his two Test matches that year he made 0, 34 and 18, and when, peremptorily, the selectors dropped him, he pledged himself to compile such a stack of runs that sooner or later they would be obliged to bring him back. Regardless of the rate at which he scored, he set his course, eliminating, along the way, those attacking strokes which contained an element of risk.

To make a success of such a scheme, Barrington needed, and possessed, immense determination and considerable talent, as well as a stubborn streak. On the occasions when he let himself go, as against Australia at Melbourne in 1966 when he scored 102 in two and a half hours, he displayed every shot in the book. There was none that he lacked. And when, sometimes, he decided to act the fool, his improvisation and impersonation were equally brilliant. But the Barrington we got to know, and came to stand by, was first and foremost an accumulator. He remained faithful to the cut, in all its varieties, and was a wonderfully deft placer of the ball on the on-side.

By adopting an extravagantly open stance, to counter the predominance of in-swing bowling, he restricted the range of his driving. To hit a half-volley between cover-point and extra-cover he needed to swivel his left shoulder from the direction of wide mid-wicket to a line outside the off stump. Not surprisingly, this was something which he was prepared to attempt only when he was well set, and even then his bottom hand remained the master.

On a day when he was not in the mood, Barrington would walk to the wicket as though delaying, for as long as possible, the dreaded moment when he took his guard. For a long time he might survive only by using his front leg as a second bat and by shuffling his back leg across the stumps as a further line of defence.

Anything intended for mid-off would go to mid-on; anything beating the bat would prompt a long and anxious examination of the pitch. To batsmen whose turn was yet to come it must have been an unnerving sight. Yet, remembering his resolution that it was only runs that mattered, he would resist the temptations of despair. As the hours passed he might offer his bat to the barrackers, but to each ball he would apply himself with every corner of his mind.

Barrington (back row, far left) with the rest of England’s side for the first Test against Australia at Edgbaston, 1961

Barrington (back row, far left) with the rest of England’s side for the first Test against Australia at Edgbaston, 1961

When, in 1965, he was dropped from the England side for taking seven and a half hours to make 137 against New Zealand at Edgbaston, he was not away for long. Suspended, as it were, for one match, he made 163 in the next, at an acceptable rate. Some were driven to distraction by his caution; others admired his sedulity; many were grateful for the runs he made.

He was at his best when England had their backs to the wall. Then, with those craggy features and that strong, thick-set figure, he was a symbol of defiance.

When asked what he thought would be the perfect start to an innings he once replied, “To find a leg-spinner bowling, and to hit the first ball, a long hop, past cover-point for four, and to hit the next, a full toss, for four to square leg. In fact, to score five fours and a three off the over.” Like many of the game’s most prolific batsmen, he liked, if he could, to have the strike, so that he always had a shrewd idea of how many balls there had been in an over. Partly for this reason, he was not the easiest of partners to run with.

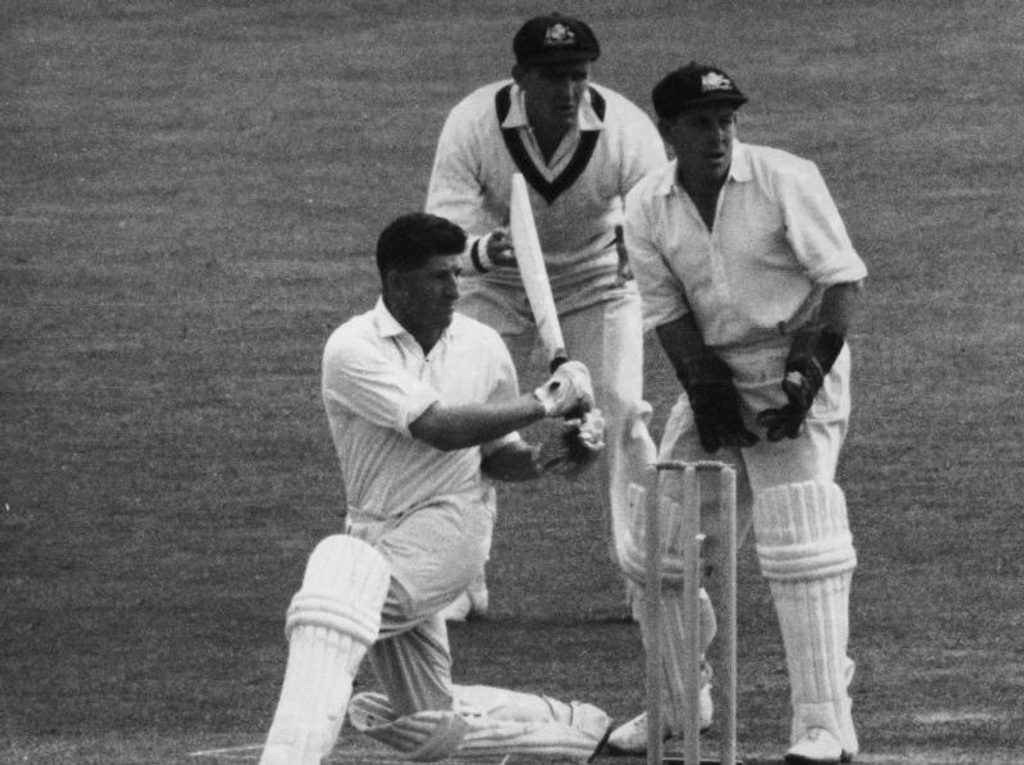

Barrington at the crease against the visiting Australians in 1961

Barrington at the crease against the visiting Australians in 1961

He was, of course, massively competent against leg-spin, which he played mostly from the crease. In the 17 innings he played against Australia when Richie Benaud was on the Australian side, Benaud got his wicket only three times. Barrington’s scores on those occasions were 83, 78 and 101. He despatched the underpitched leg-break between square-leg and wide mid-on with the utmost certainty, and there can have been few better at spotting the googly.

Against the fastest bowling, his play was a curious mixture of courage and apprehension. Without finding that it afforded him much pleasure, there were times when he displayed great fortitude against Hall and Griffith, bowling at their fastest and shortest. His hooking of the bouncer was then truly defiant.

Barrington’s best innings against West Indies were played out there. He got a hundred in each of the first two Tests in 1959-60 and another in the first Test in 1967-68. His record against them in England was less impressive. He accused Griffith of being a thrower at the end of the West Indies tour of 1963, and when West Indies came to England next, in 1966, Barrington’s nerves for once got the better of him. After failing in the first two Test matches he took a long rest from the game.

As a result, his next encounter with Griffith, in Port of Spain at the beginning of 1968, was a test of character quite as much as technique. To his undying credit Barrington made 143, his highest score in a Test match against West Indies. Griffith, who was never one to hold his fire, greeted Barrington with a regular barrage of bouncers, without succeeding again in breaking his resistance.

Barrington batting against Australia in Sydney, 1963 — the talismanic batsman was prolific Down Under

Barrington batting against Australia in Sydney, 1963 — the talismanic batsman was prolific Down Under

Barrington’s happiest hunting ground was Australia. Here, on his two visits, he had prodigious success, especially in 1962-63 when his aggregate of 1,451 runs (average 85.35) had been exceeded, on an MCC tour, only by Walter Hammond in 1928-29 (1,553 runs at an average of 91.35).

Barrington’s scores on that tour are an indication of his consistency. They were: 24, 0, 44, 104, 219 not out, 19, 183 not out, 78, 23, 52, 35, 0 not out, 35, 23, 63, 132 not out, 33, 67, 101 and 93. These he followed with a century in the first Test against New Zealand. Only Herbert Sutcliffe (66.85) has a better average against Australia than Barrington’s, which is 63.96.

As might be expected, Barrington plundered the bowling in India. I never saw him more crestfallen than at Ahmedabad in 1963-64 when, with four Test matches still to be played, he broke a finger in the last moments of a drawn game against West Zone. He was attempting a catch at slip. It was soon obvious that he would miss the remainder of the series, a realisation which prompted a characteristic comment – “And to think of all those Test match runs that’ll be going a’begging.”

In South Africa, too, there was no stopping him when he was fit. Among Englishmen, only Denis Compton, Len Hutton, Jack Hobbs and Peter May have scored more runs in a South African season.

That Barrington’s record was appreciably better overseas than in England could have been due to the longer rest between games which he had on tour. Such was the concentration which went into each of his innings that he usually benefited from a spell on the sidelines.

Only three times in England did he pass 2,000 runs in a season. Of his 20 Test match hundreds only six were at home. And in Championship matches he never passed 1,500 runs. But the most innings he ever played in a season for Surrey, in Championship games, was 41, and in the last eight years of his career he only twice played over 30. Hobbs, Sandham and Hayward frequently played over 50. Whereas Barrington averaged 93 at Adelaide and 94 at Melbourne and 85 at Bridgetown, his average at Lord’s was a mere 31, while at The Oval it was 42.

There is no doubt, I think, that he was a more vital member of England’s side than Surrey’s. The slower tempo of Test cricket suited his philosophy. It fitted in with his plan for progress. He was more in his element saving matches than winning them, so it was no coincidence that Surrey never won the Championship when he was at his best, while England seldom lost a game.

Barrington in action for Surrey, 1965

Barrington in action for Surrey, 1965

Barrington’s aptitude for cricket did not end with his batting. He was a versatile fielder, with a good arm and a quick eye. For Surrey he spent most of his time at slip; for England he was generally further from the bat. To his own bowling he was all over the place. Yes, his own bowling. Had he been born in Australia I am sure he would have become a considerable all-rounder. In England, most young cricketers who join a county as a leg-spinner, either finish up as a batsman or fail, often for want of encouragement, to make the grade. In Australia, at the time when Barrington was launching his career, no side was seen to be complete without at least one leg-spinner in it, and Barrington, though he bowled so little, was quite as good as some who played regular Sheffield Shield cricket.

As an Englishman, Barrington was given the opportunity to take only 273 wickets, and that is a reflection on, if not an indictment of, the captaincy as well as the methods of the age in which he played. He was generally put on as a last resort, coveted though his victims often were.

In Test cricket he took 29 wickets. These included Sobers (twice), Nurse, Hunte, Walcott, McMorris, Camacho (twice), Walters, Cowper, Davidson, Umrigar and Borde. Yet several whole series passed without Barrington, who greatly enjoyed his bowling, being asked to bowl. All the while the seamers were taking an increasingly firm and unwelcome hold on the game.

Off the field, Barrington was a most amusing companion. Gone was the introspection of his batting, if not the determination which was so much a part of it. I recall an incident which illustrates his attitude to life, yet which had nothing to do with cricket. We organised, one Christmas Day in Adelaide, some afternoon golf, as an aid to digestion. With the help of various sweepstakes and an auction, Barrington became aware that he could win himself quite a substantial sum of money if he played to his handicap. As a result, no one drank less with the turkey or left earlier for the course or applied himself more painstakingly to the business of finishing first. Bradman, on his home course, Dexter, Graveney and Cowdrey were among those whom Barrington beat that day. He won the competition by a street.

His sense of humour extended to his reaching no fewer than four Test hundreds with a six – at Melbourne, Adelaide, Durban and Trinidad. The stroke he used for the purpose was a violent pull which took everyone completely by surprise and invariably ended a protracted period of defence. He was a splendid mimic, the Australian, Ken Mackay, being among those he took off with great skill. Nor does anything go on under the bonnet of a motor car which mystifies him.

Sometimes, to hear him talk, you might suppose he looked upon slow batsmanship as one of the deadly sins. But it is a trait of captains and batsmen that they cast off their inhibitions when they retire. And Barrington, by the time he did so, had made for himself an extraordinary collection of batting records. Of these his own personal favourites are shared with no one. He alone has made a Test hundred on every Test match ground in England and in every Test-playing country of the world.