Jim Laker, still the only man to take 19 wickets in a Test, was born in February 1922. After his death in 1986, this tribute, full of fascinating technical insight, was published in the 1987 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack.

Read more features from the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack

Previous Almanack feature: Fiery Fred: The incomparable Fred Trueman – Almanack tribute

In the early 1950s Everest had not yet been tamed. It stood alone among the high places of the world. Now, more than thirty years later, its climbs are still the test for real mountaineers, but even as they prove the efficacy of their thermal underwear, Everest seems to have shrunk. Hillary and Tensing have been followed to the top.

Down below, in kinder, greener conditions, the underwear is not for keeping out the cold but for mopping up the sweat. Even so, on the cricket field, conditions of wind and wear, of dust and damp, still must be watched and taken into account.

There, however, Jim Laker’s achievement, nineteen wickets in a Test match, has not attracted followers. Nor may it ever be beaten. Twenty wickets in a match is still Everest, far more significant in a cricket context than any record for batting or even for all-round excellence. Laker’s nineteen looks less and less repeatable as the seasons pass.

Jim Laker (1922 – 1986) playing for England against South Africa at the Oval, 1951

Jim Laker (1922 – 1986) playing for England against South Africa at the Oval, 1951

With Lock, the most avaricious of bowlers, bowling 69 overs at the other end for Burke’s first-innings wicket; the one that got away from Laker. Nor should it pass notice that Statham and Bailey, both unquestioned occupants of the hall of fame, sent down 46 overs between them without a strike. Even if you accept that the 1956 Australians were not one of the best sides from that country, there were great cricketers in that team; Harvey, Miller, Lindwall, Benaud. In truth, even though it happened, we can describe Laker’s feat only as incredible.

At 34, Laker was at the peak of his powers in 1956. As a slow off-break bowler in the classical tradition, he was the unchallenged master of his craft. His confidence soared. Surrey were in their run of seven successive Championships, then the only pudding for proof at county level.

Stuart Surridge, the captain who made Laker, allowing his bowler the luxury of being able to live without ever needing to doubt his own ability, had an unshakeable belief in the destiny of Surrey and its players. Furthermore, Laker had something of a score to settle with the Australians.

In 1948, during the last chapter in the Bradman saga which had earlier featured bodyline and all that, England were desperate for a victory; but at Leeds; where Australia were set to score 404 to win in 344 minutes, he had failed to bowl them out in the fourth innings. Afterwards he would talk gently about dropped catches and the lack of spin support, there being only Compton’s occasional chinamen available. At Lord’s though, where this particular England defeat hurt more than most, there was a suspicion that when the crunch came, Laker was chicken.

After Laker’s failure at Leeds, off-spinning was relegated to third place in the spinning hierarchy behind the left-arm spinners and leg-spinners. Not that it would have mattered who had bowled in the Test in 1948, because at The Oval England were bowled out for 52.

Jim Laker showing schoolboy fans how to hold a cricket ball

Jim Laker showing schoolboy fans how to hold a cricket ball

Laker won caps in the years that followed, but first Tattersall and then Appleyard kept him out of the England XI. Both were fine bowlers, but neither was orthodox like Laker. Tattersall held his forefinger, a long one, alongside the seam and pushed his off-spinner in a manner that helped him disguise the away-swinger. Appleyard exploded on the scene as a fast-medium bowler with a deadly off-cutter. Later he slowed down and learned to spin while never losing his quick bowler’s action.

We have seen the same development since in Greig’s bowling. Both Tattersall and Appleyard were deadly on wet wickets. Because of their actions, preceded by a longer run than that of Laker and his followers, they had the potential for an increase of pace and therefore penetration. But Laker, too, was a fearsome opponent on wet wickets. His action, so grooved in its approach, so upright in delivery, was an instrument on which he could play the pace variations that he wanted, although never reaching medium pace.

Laker’s principal asset, and the one he looked for first among spin bowlers in his later coaching and commentary career, was power of spin. His action, a slow bowler’s action, enabled him to deliver the ball spun by the fingers and snapped forward with the wrist. He charged the ball with more menace than his rivals and, I suspect, almost all his followers. Not that Laker lacked an away-swinger or the ability to use the breeze from long leg. He was always reluctant to switch his slip to lock up the leg-trap, recognising that no matter how responsive the pitch, even the finger-spun ball might hustle on without deviation, taking the outside edge as a batsman played for the turn.

In another important aspect Laker was pre-eminent, certainly among his contemporaries. Not only did he have equal ability over and round the wicket, but he combined his with the shrewdest understanding of which batsman could be better discomforted by a change of angle. On good pitches, on-side players would be attacked from round the wicket on the basis that they, if they played across the line of that angle, be candidates for a catch at the wicket or slip. Similarly, by using the full crease from over the wicket, he had a chance of getting through the off-side driver, or at least of taking his inside edge. When the ball was turning, the geometry spoke not only for itself but also to umpires, who would give leg-before decisions on the front foot only if the bowler was going round the wicket.

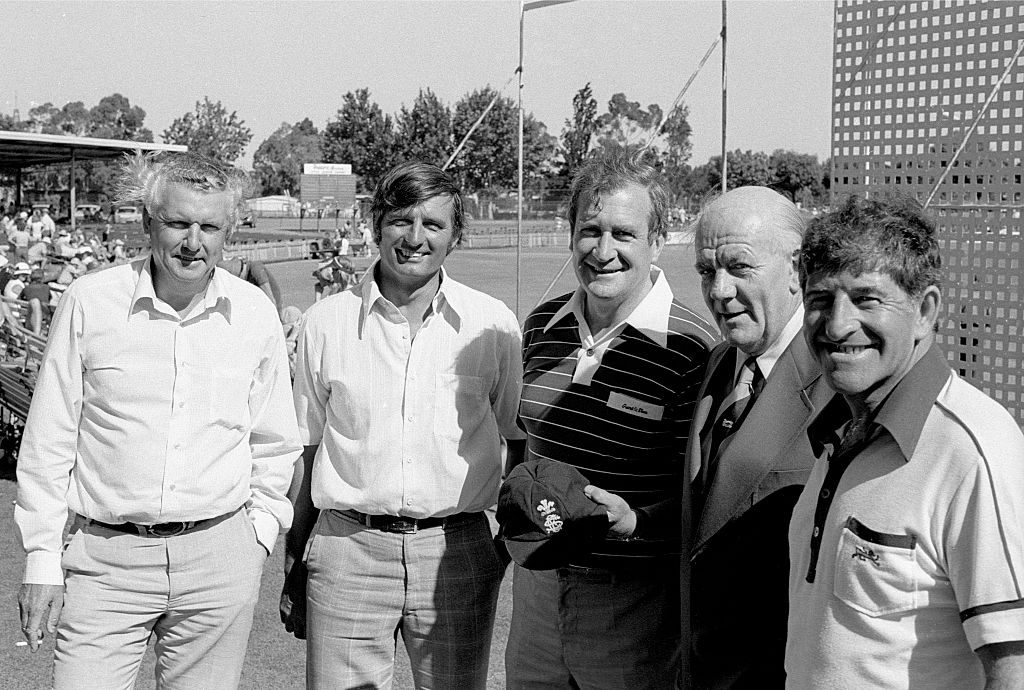

Former Surrey players (from left) Peter Loader, Ron Tindall, Jim Laker, Tony Lock and Ken Barrington, 1978

Former Surrey players (from left) Peter Loader, Ron Tindall, Jim Laker, Tony Lock and Ken Barrington, 1978

Laker’s ability in this respect – and one not given to the leading Test wicket-taker of this type, Gibbs, who could not bowl round the wicket – depended on the position of his body. Operating round the wicket, he clung to the leg stump with his backside, his final stride short enough to give him perfect balance, enabling him to make maximum use of his six-foot frame.

Because of this perfect action, he was able to maintain not only his tight control over direction and length but also those subtle variations in trajectory, in the loop, which differentiated Laker from one breed of lesser performer. Only his splendid control gave Surridge, his captain, crowding helmetless in the danger zone, the courage to walk forward from short leg. Indeed, Laker was sure that some catches were missed because his close men were too keen.

Generations overlap, but the second overlap will inevitably take the players and their game into new territory, thus rendering comparisons deceptively, dangerously, impossible. In Laker’s time pitches were uncovered, albeit progressively less so. Outfields were less like carpets. There was less grass on the squares and what there was, was cut shorter. The science of pitch preparation was in its infancy. Groundsmanship is not so unlike farming that we can fail to notice that in Laker’s time there was no embarrassing food mountain.

No batsman then wielded heavier willow than 2lb 7oz, and most bats were 2lb 4oz. Pads were less padded, and technique against the off-break was not so well developed that batsmen could avoid opening the gate; with the result that an off-break, when properly spun, could go through to bowl a highly rated player.

Match balls were hand, not machine-stitched and less well dyed, although they did keep their shape better. If you gripped these balls tight with the fingers across the seam and ripped them across it, the skin on the fingers was eventually torn. Laker soaked his right forefinger in surgical spirit at the start of the season to harden the skin, but even so it tore, the split eventually deepening until it bled. Each spinner had a different solution to the problem, some even stopping giving the ball such a tweak. Not Laker. Never. He would use a concoction called Friar’s Balsam, which seemed to give him antiseptic protection until a corn developed, although later in the season that corn would itself split and bleed.

Laker’s 46 Tests for England saw him return 193 wickets

Laker’s 46 Tests for England saw him return 193 wickets

It should not pass notice that in the second innings of that famous Old Trafford Test, Laker bowled 51 overs and two balls with hardly a break. Yet in all of the 1956 season he bowled only 959 overs: only because it was not uncommon for spin bowlers to break 1,000 or even 1,250 overs a session.

Laker’s spinning finger thickened with arthritis, noticeably so when compared with the same digit on the left hand, and from time to time, when confronted by these problems, he was, perhaps inevitably, not keen to fill the stock-bowling role as a Surrey match eased gently towards a draw. Like the voice of Callas, a spin bowler’s finger demanded judicious use.

No cricketer could have made an impression on the game as vividly as Laker without having the personality to deploy his talent. He might have gone to Surrey from Catford, but Jim Laker was the archetypal dry Yorkshireman. If his tongue could cut, his eye was keen. His humour depended on the detached observance of the passing scene, never better illustrated than in his story of the journey home after that Test, when he sat in a Lichfield pub alone and unrecognised whilst others celebrated what he had done. Nor were his years in banking wasted, for he invested shrewdly when he finally settled in Putney. After his brief flirtation with industry, commentating for television, together with his articles and books, kept him financially afloat. Cricket apart, he was not looking for the big one.

Not all cricketers travel contentedly through the rest of their lives. To all appearances Laker was one of the lucky ones. Perhaps an inner awareness of his stupendous achievement as a player, the bestest with the mostest, gave him lasting satisfaction. When he came back from his next winter tour in South Africa to pick up yet more awards, he found that the legislators had begun to interfere with the right of captains and bowlers to place their fielders at will. They have made it harder for anyone to repeat my success, he told one audience, and as so often in his cricketing judgment, Laker is likely to be right. When shall we look upon his like again?