When Ranjitsinhji first emerged in English cricket in the mid-1890s, nobody had ever seen anything quite like his stylish strokeplay. His record-breaking season in 1896 earned him a Wisden Cricketer of the Year award.

Curiously, the Almanack profile did not mention that Ranji had made his Test debut in 1896, scoring 235 runs at 78 against Australia. He played in 15 Tests in all, scoring 989 runs at 44.95.

Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji, the young Indian batsman who has in the course of four seasons risen to the highest point of success and popular favour, was born on the 10th of September, 1872. When he first began to be talked about, the statement gained currency that he knew nothing whatever of cricket before coming to England to complete his education, but on this point Ranjitsinhji has himself put the world right.

It is true that when he went up to Cambridge he had nearly everything of the real science to learn, but he had played the game in his schooldays in India, and was by no means such an entire novice as has sometimes been represented. It was in 1892 that the English public first heard his name, and there is little doubt that he ought that year to have been included in the Cambridge eleven.

Naturally then he was not then the great batsman he has since become, but he made lots of runs in college matches, and was already a brilliant field. The authorities at Cambridge perhaps found it hard to believe that an Indian could be a first-rate cricketer, and at the complimentary dinner given to Ranjitsinhji at Cambridge on September 29th – when his health was proposed by the Master of Trinity – Mr FS Jackson frankly acknowledged he had never made so great a mistake in his life as when he underestimated the young batsman’s powers.

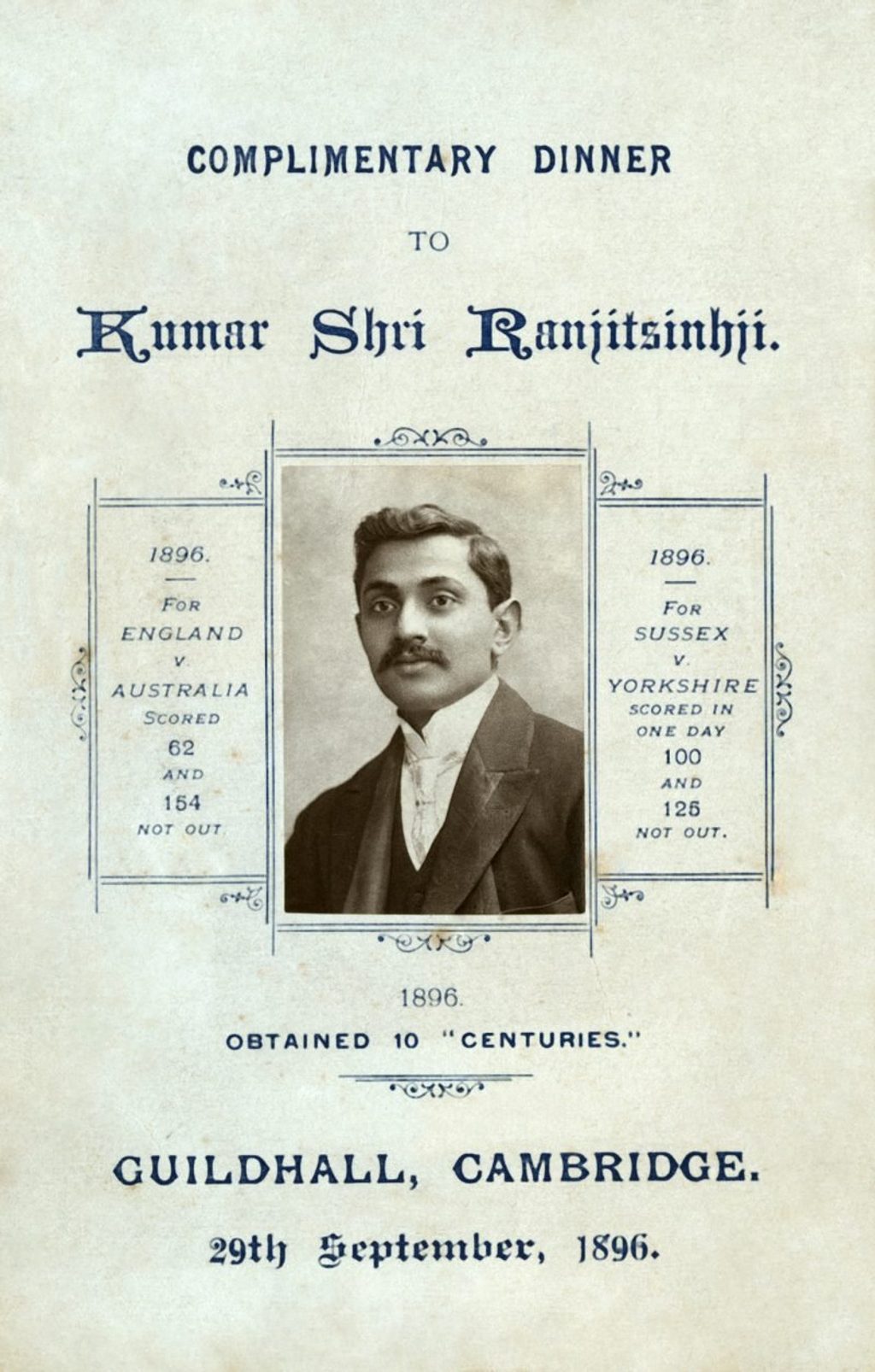

The front cover of the eight-sided menu card for a Complimentary Dinner for Ranjitsinhji, attended by 300 leading cricket club representatives and friends, at the Guildhall of Cambridge on September 29, 1896

The front cover of the eight-sided menu card for a Complimentary Dinner for Ranjitsinhji, attended by 300 leading cricket club representatives and friends, at the Guildhall of Cambridge on September 29, 1896

However, Ranjitsinhji’s opportunity came in 1893 when, in his last year at the University, he, to his great delight, gained a place in the Cambridge eleven. It was not his good fortune to do much against Oxford at Lord’s – getting out for nine in the first innings, and without a run in the second – but on the whole he batted very well, scoring 386 runs with an average of 29 and coming out third in the Cambridge averages.

Moreover, he had the honour of being chosen for the South of England against the Australians at The Oval, and though his real greatness as a batsman was as yet scarcely suspected, he made himself a very popular figure in the cricket world, his free finished batting and brilliant work in the field earning him recognition wherever he went.

Having left Cambridge, and not being yet qualified for Sussex,his opportunities in 1894 were very limited, and in first-class matches he only played 16 innings. Still he did well, averaging 32 with an aggregate of 387 runs. For the immense advance he showed in 1895, it is safe to say that very few people were prepared.

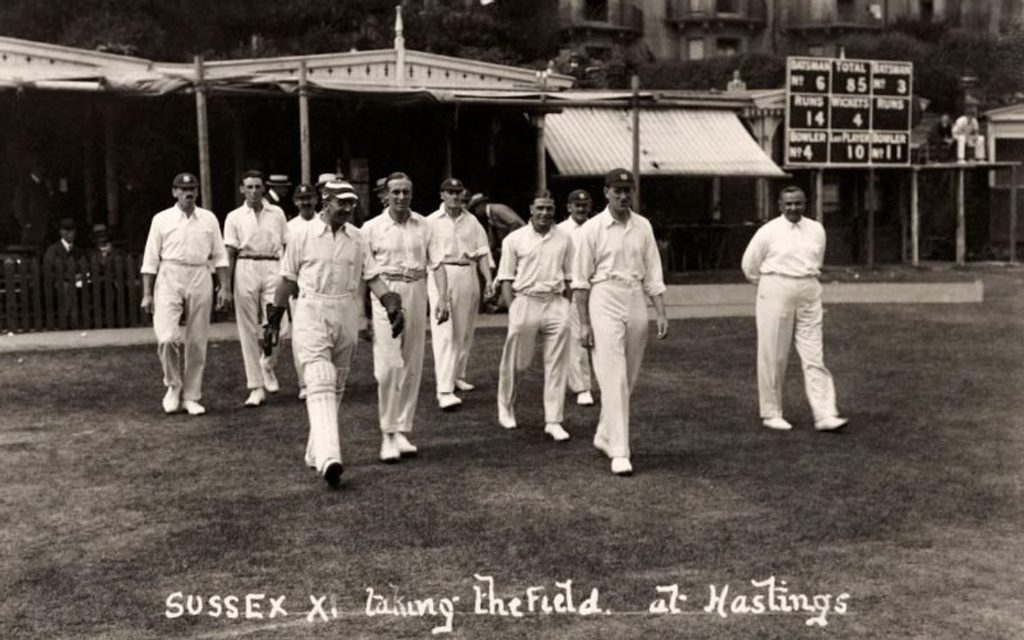

The Sussex county team taking the field at Hastings, circa 1919. Ranjitsinhji is walking on his own, far right

The Sussex county team taking the field at Hastings, circa 1919. Ranjitsinhji is walking on his own, far right

Qualified by this time for Sussex, he made a truly sensational first appearance for the county against the MCC at Lord’s, scoring 77 not out, and 150, and almost winning a match in which Sussex had to get 405 in the last innings. From this time forward, he went on from success to success, proving beyond all question that he was now one of the finest of living batsmen.

In the first-class averages for the year, he ran a desperately close race with AC MacLaren and WG Grace, scoring 1,775 runs with the splendid average of 49. Of these 1,775 runs all but nine were obtained for Sussex, his energies being so entirely devoted to the county that, rather than stand out of the Sussex and Hampshire match, he declined the invitation of the MCC committee to appear for the Gentlemen at Lord’s.

What Ranjitsinhji did last season is set forth in full detail on another page of the Wisden Almanack, and there is no need to go twice over the same ground. It will be sufficient to say that he scored more runs in first-class matches than had ever been obtained by any batsman in one season, beating Mr Grace’s remarkable aggregate of 2,739 in 1871. While giving the Indian player, however, every credit for his extraordinary record, it must always be borne in mind that while he averaged 57 last season, Mr Grace’s average in 1871 was 78.

The coronation of Prince Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji or Ranji of Nawanagar, riding in his silver carriage, at the Durbar in Delhi, circa 1907

The coronation of Prince Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji or Ranji of Nawanagar, riding in his silver carriage, at the Durbar in Delhi, circa 1907

As a batsman Ranjitsinhji is himself alone, being quite individual and distinctive in his style of play. He can scarcely be pointed to as a safe model for young and aspiring batsmen, his peculiar and almost unique skill depending in large measure on extreme keenness of eye, combined with great power and flexibility of wrist.

For any ordinary player to attempt to turn good length balls off the middle stump as he does, would be futile and disastrous. To Ranjitsinhji on a fast wicket, however, everything seems possible, and if the somewhat too-freely-used word genius can with any propriety be employed in connection with cricket, it surely applies to the young Indian’s batting.