Majid Khan was an enchanting batsman for Pakistan who made his name while still in his teens. His role in Glamorgan’s 1969 County Championship triumph earned him a Wisden Cricketer of the Year award.

Majid Khan played on for Glamorgan until 1976 and for Pakistan until 1982/83. In Tests, he hit 3,931 runs at 38.92 in 63 matches.

In its young life the Muslim state of Pakistan has produced many uncommonly fine cricketers. The titans of the early years have been succeeded by equally brilliant players able to stand comparison with the world’s best. Among them is Majid Jahangir Khan, a sporting thoroughbred raised in Kipling’s ancient city of Lahore, and now the champion of Glamorgan. In October he entered Cambridge University for three years.

Born at Jullundur, in the Punjab, on September 28, 1946, Majid had the considerable advantage of a famous father, an athletic frame and an eye and passion for cricket. Dr Jahangir Khan was a fast bowler for India and Cambridge, and was wont, so legend has it, to lapse into philosophical verse while fielding in the slips on the less successful occasions.

Open Account Offer. Up to £100 in Bet Credits for new customers at bet365. Min deposit £5. Bet Credits available for use upon settlement of bets to value of qualifying deposit. Min odds, bet and payment method exclusions apply. Returns exclude Bet Credits stake. Time limits and T&Cs apply. The bonus code WISDEN can be used during registration, but does not change the offer amount in any way.

Asad, Majid’s elder brother, was an Oxford blue in 1968 and 1969, and took seven Australian wickets for 84 with his off-breaks for the combined Oxford and Cambridge XI at Fenner’s. Javed Burki, a first cousin, captained Pakistan in England in 1962 and was a leading Oxford batsman for three seasons.

Father preferred not to coach Majid, but, what was more important, encouraged him to enjoy his cricket at all levels. Despite an inevitable tightening-up of his technique and some professional polishing after two years in the County Championship on top of Test experience, Majid, of the quick eye, darting footwork and challenging disposition, remains an exciting batsman able to achieve a proper balance between attack and defence.

At his first school – St Anthony’s, Lahore – he was considered too small for the team, but Aitchison College (the first Nawab of Pataudi was one of its most distinguished players) took him in the first XI at the age of 13 and kept him there for four years.

He was still at school in the season of 1961/62 when he made his first-class debut for Lahore against Khairpur Division, scoring 111 not out and taking six wickets for 67 with his fast bowling. Surely no cricketer anywhere can have announced himself more firmly. Triumphs followed at Punjab University, including a performance which defied description against Karachi in the National Ayub zonal tournament.

Majid batted at No.5. The first three were out for three, and soon it was 5-4. Majid then scored a not out double century to win the match. Lahore Board, a Schools side captained by Younis Ahmed, now of Surrey, reached the final of the Ayub Trophy, but by then Majid was a fully fledged Test batsman.

After a tour of England with the Eaglets in 1963, in which he topped the bowling averages, Majid was chosen for the first of his seven Tests to date, against Australia at Karachi. He was 18 years 26 days old, the ninth youngest in the history of the game, and the fifth youngest for his country, to play in a Test. Majid was first a bowler at that time, and true to his startling career, he took Bill Lawry’s wicket in his second over. Lawry also was out to him in the second innings, and a third victim was Brian Booth. All fell to bumpers, but Bobby Simpson, Australia’s captain, questioned their legality.

Majid sounded the opinion of Khalid Ibadulla, the experienced Warwickshire all-rounder who made 166 in the same match, and, as a result, Majid there and then decided to eliminate his bumper and change his bowling style.

Majid Khan in action for Pakistan during their tour match against Kent at Canterbury in July 1967

Majid Khan in action for Pakistan during their tour match against Kent at Canterbury in July 1967

Partly as a result Majid did not go to Australia and New Zealand, but he was back in Pakistan’s side for the home series with New Zealand in 1965, and this time as a batsman. At Lahore, so often the scene of his best cricket, he made 80. A year later, still experimenting with his bowling action, he badly pulled a back muscle, an injury which was aggravated at Lord’s in 1967. The cure was to sleep on hard boards, and the habit grew so that to this day he prefers to lie on the floor. He abhors a soft bed.

Majid’s high potential was much in evidence during MCC’s Under 25 tour of Pakistan in 1967. In the first unofficial Test at Lahore he made 100 not out and 57, and in the second at Dacca, when Pakistan followed on, his stand of 167 in two hours, 25 minutes with Asif Iqbal undoubtedly saved his side from defeat. Majid’s share was 95, and he reached such a high standard of technical efficiency and power that his mixed fortunes in England later that year were hard to understand. While he scored freely and brilliantly in the other fixtures he managed only 38 runs in the three Tests, including 17 in one innings at Trent Bridge. Such is the perversity of form in cricket.

In all matches he made 973 runs, the highest aggregate, with an average of 42.30, second only to his captain, Hanif Mohammad. Majid hit centuries against Glamorgan, Sussex, Middlesex and Kent, and with the exception of Asif’s in The Oval Test, no innings that season was more spectacular than his 147 not out at Cardiff. He made his runs in eighty-nine minutes, and his thirteen sixes were a record in England. Only John Reid, who hit fifteen sixes for Wellington against Northern Districts, in New Zealand in 1962/63 can better it in world cricket.

Five sixes came in one over against Roger Davis, the off-break bowler. (Odd that a season later Gary Sobers should take six sixes in one over from Malcolm Nash on the same ground.) Majid’s first 100 in 61 minutes was the fastest of the season, and it was small wonder that Glamorgan’s first priority was to induce Majid to join them.

He did so and by mid-season in 1968 was fulfilling Glamorgan’s highest hopes. He ended his first year with 1,258 runs, and it was significant that Glamorgan rose from fourteenth to third place. Back home, Majid often showed splendid form against England in the series wrecked by political upheaval. Once again he did well at Lahore during a crisis, and he emerged, despite all the distracting off-field activities, a responsible and adult Test batsman.

As the 1969 season developed into a triumph for Glamorgan, Majid’s success was synonymous. It became almost an inexcusable cliche to describe his batting as sheer magic, but so often it was exactly that. While it is true that Glamorgan’s victory was essentially one of good leadership, team work and the ability to catch everything above ground, Majid was able to add a glow of inspired individualism. At slip (with no reputation as a verse speaker!) he was part of the close-to-the-wicket quartet of Roger Davis, Peter Walker and Bryan Davis, whose combined stretching hands must have looked like a greedy octopus to the poor batsman.

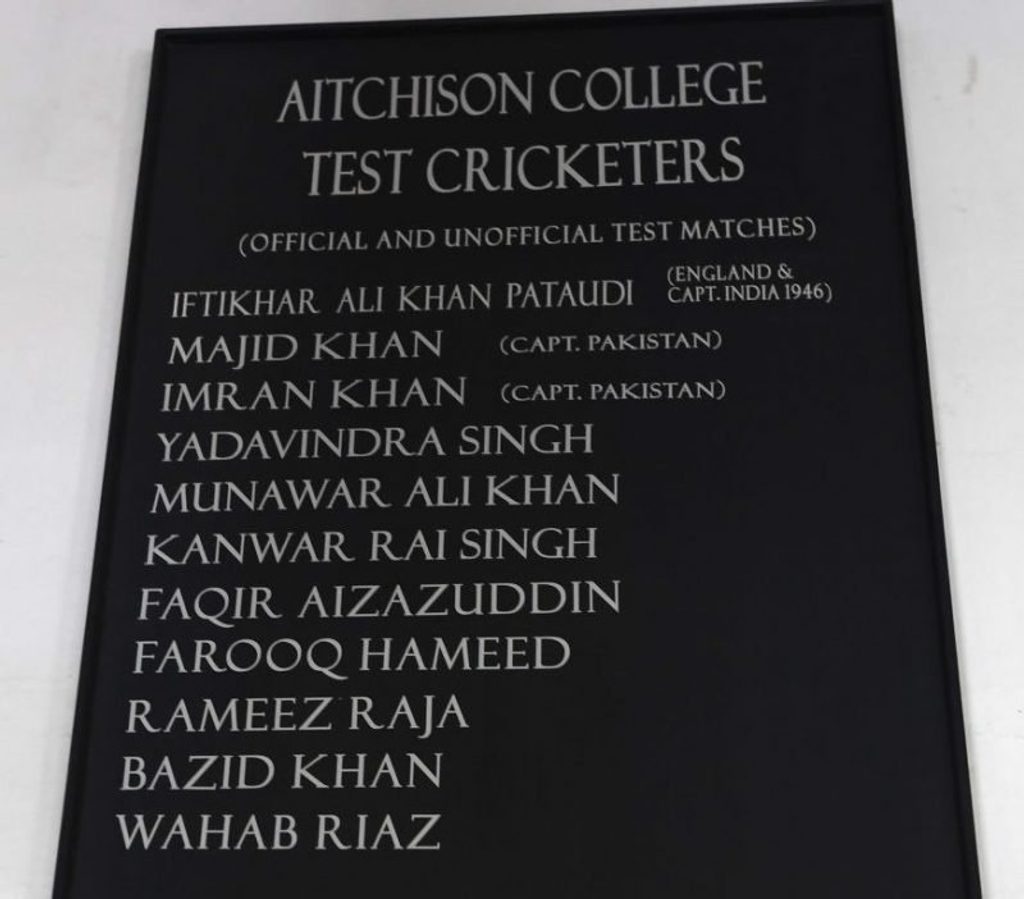

An honours board at the Aitchison College cricket ground pavilion, listing the names of its players who’ve gone on to play Test cricket

An honours board at the Aitchison College cricket ground pavilion, listing the names of its players who’ve gone on to play Test cricket

When he conjured 156 off Worcestershire in the crucial match on a none too easy pitch at Cardiff – an innings which he regards as his best to date – a lilting Welsh voice was heard to exclaim: “I’d pay five bob just to see this chap take guard!” A day later, with the crowd celebrating the final victory, the cry went up “Majid … Majid … Majid.” The recital of a mere name became almost an incantation, a hymn of praise. They were not satisfied until Majid, who wants to be known as MJ Khan at Cambridge, pledged his return to Wales.

He took his adulation calmly. Indeed, with apologies to Colin Cowdrey, his team-mates have dubbed him Kipper because he is so relaxed before he bats. His philosophical attitude to the game undoubtedly helps. “When I go into bat” he says, “I regard it as a personal battle with the bowler. The other ten on the field are his helpers. I always believe the ball is there to be hit, and it is wrong to change techniques for different types of wicket. I feel it is the most certain way to get out to change your methods. I always try and play the way it comes naturally to me. I have been extremely happy with Glamorgan, who are a friendly side. The Welsh people I have found to be marvellously hospitable, and I plan to return to play for three or four seasons after my Cambridge days.”

Tony Lewis, Glamorgan’s captain, regards Majid’s loss, if only temporary, as catastrophic, and it will be fascinating to watch his influence on English university cricket, which is badly in need of a tonic and self-reassurance.