Graham Dilley was once described as the fastest white bowler in the world by Clive Lloyd. Yet his Test career was one of frustration and fits and starts. His Wisden obituary in 2012 recalled his ups and downs.

Dilley, Graham Roy died of cancer on October 5, 2011, aged 52.

In the days immediately after the death of Graham Dilley, it was possible to survey the media coverage and lose sight of the fact that he had been – when form and fitness coalesced – a fast bowler blessed with immense talent. Instead, what dominated the reports and reminiscences was his batting on a Monday afternoon in Leeds 30 years earlier. Yet Dilley was much more than the raucous bit-part who spent an hour and 20 minutes throwing the bat with Ian Botham amid the drama of Headingley ‘81.

Graham Dilley took 138 Test wickets from 41 matches

Graham Dilley took 138 Test wickets from 41 matches

Able to bowl at high pace, with devastating late swing, he was a prospect no batsman relished, especially in his mid-1980s heyday, when he fulfilled the promise that had been identified by Kent while he was playing for Dartford CC a decade earlier. But persistent injury problems, the whims of selectors and a gnawing lack of self-belief meant his golden period was a short one. He still took 138 wickets at 29.76 in 41 Tests between 1979 and 1989, although it said a great deal about England’s chronic underachievement that he was on the winning side only twice.

Having played a minor role in Kent’s 1978 Championship success, he shared in two further title wins after his move to Worcestershire in 1987, and in retirement became a respected coach. He found a niche at Loughborough University, where he belied his laid-back image to become a stickler for punctuality, hard graft and rigorous fitness standards – even if his next cigarette break was seldom far away.

Dilley was training as a diamond cutter in Hatton Garden before he made his debut for Kent in 1977. At 6ft 4in, with a mop of blonde hair, a loping run that ended in a huge delivery stride, and a slingy action, he was instantly eye-catching. His early progress was unspectacular, but there were plenty of experienced pros at Canterbury who knew better. “He was bowling in the corridor of uncertainty before anyone knew it existed,” said brother-in-law and former team-mate Graham Johnson.

In 1979, he took 49 wickets and was selected for England’s post-Packer tour of Australia. At Perth, in the First Test, Dilley was handed the new ball in the hope he could harness the WACA’s bounce, but he took only three wickets (his single success in the second innings gave lasting pleasure to lovers of cricketing marginalia: Lillee c Willey b Dilley). In all first-class tour games, he struck only seven times. “That’s £1,000 a wicket,” grumbled manager Alec Bedser.

There was more dubious man-management in the Caribbean the following winter, this time from his captain Botham. “When Dilley bowled a few bad balls, or things didn’t go well for him in the first Test in Trinidad, Botham’s idea of dealing with it certainly didn’t match my own,” Chris Old remembered. “There were a series of leg-pulling remarks that Botham actually meant in a serious way. I could see from Dilley’s demeanour and his body language that he was suffering even more.” Dilley ended the trip wearing his captain’s bowling boots after the toes of all the pairs he had taken on tour were shredded on the hard grounds by the back-foot drag in his delivery stride.

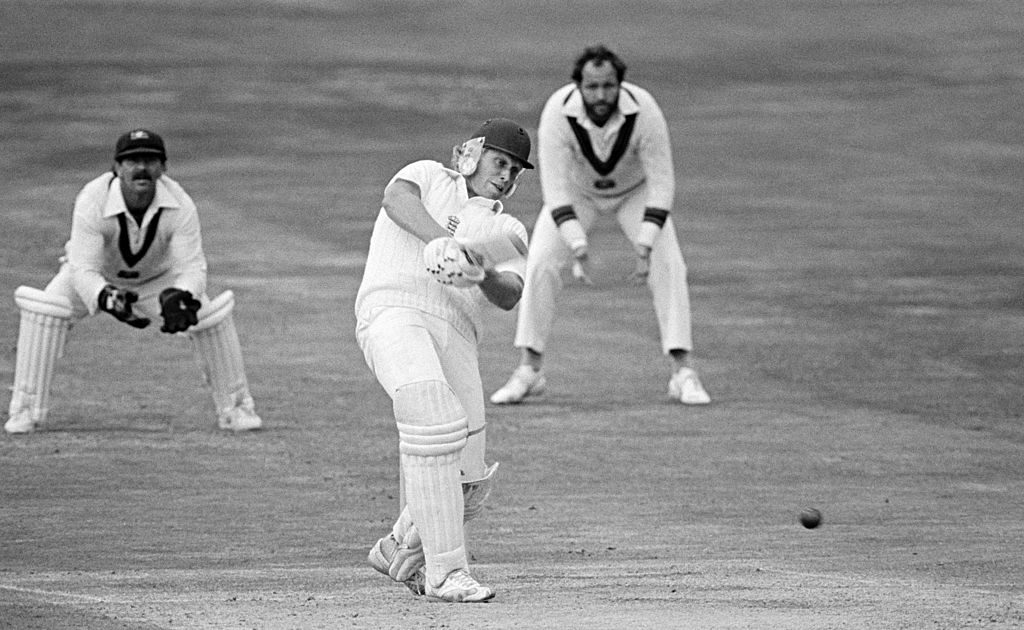

Graham Dilley on his way to 56 at Headingley, July 1981

Graham Dilley on his way to 56 at Headingley, July 1981

A four-wicket haul in the fifth Test, at Sabina Park, prompted Clive Lloyd to call him the fastest white bowler in the world, and he remained in the team for the defence of the Ashes in 1981. With 12 wickets in the first two Tests he was an automatic choice for Mike Brearley’s return as captain at Headingley, but he bowled poorly and became the butt of criticism from the Leeds crowd. By the time he walked out to bat on the fourth afternoon, with England 135 for seven following on and still trailing by 92, he was convinced he would be dropped. On the way out he asked Old for advice. “Just have a go,” came the reply.

One of the game’s enduring myths is that Botham greeted Dilley with the words “Let’s give it some humpty,” igniting their partnership from that moment. If true, it was Dilley who paid more heed, scoring 22 of the first 27 runs they added; at tea Brearley gently teased Botham for his slow scoring. As Botham’s innings quickly gained momentum, the left-handed Dilley’s method was simply to plant his front foot around leg stump and swing cleanly. Sometimes he missed, more often he made thunderous contact. “As a batsman he was not unlike Stuart Broad,” Brearley said. He made 56 – his highest Test score – and the pair added 117 in 80 minutes before Dilley played on to Terry Alderman.

Dilley (right) with John Emburey (left) and Ian Botham (centre) after the first Test against Australia in Brisbane, November 1986. Dilley took 5-68 in Australia’s first innings

Dilley (right) with John Emburey (left) and Ian Botham (centre) after the first Test against Australia in Brisbane, November 1986. Dilley took 5-68 in Australia’s first innings

He had a cameo role the next day, holding a steepling Rod Marsh hook just in front of the rope at fine leg, but his gloomy forecast proved correct and he did not play in the fourth Test at Edgbaston. In a set of circumstances that summed up his international career, he was included in the twelve – even though a decision had already been taken that he would not play – but then suffered a shoulder injury at Derby and did not even travel to Birmingham. Shortly after his Headingley heroics, he was playing for Kent Second Eleven.

But Dilley’s action – in his final stride a batsman could count the studs on the sole of his boot – put a strain on his body. Some medical opinion thought he would not play again when he missed the whole of the 1984 season after a neck operation, but he regained form and confidence playing for Natal in 1985-86, and his most successful spell for England began as part of Mike Gatting’s all-conquering team in Australia in 1986-87. In the first Test, at the Gabba, his five for 68 helped England take a stranglehold on the series.

Back home he performed well against Pakistan, but was then omitted from the first two Tests of the winter series against the same opponents. Journalist Graham Otway recalled: “I was in my room in Lahore typing a piece when he knocked on my door, burst in and said, ‘I’ve just been dropped and I need to kick something.’ He spent the next half-hour doing just that to the furniture.” Later that winter, in New Zealand, Dilley completed an entire series for only the second time and, at Christchurch, took six for 38, his best Test figures, gleefully exploiting a pitch prepared specifically for Richard Hadlee. In the second innings, however, as England strove in vain for victory, he was fined £250 after swearing loudly when two appeals for catches were turned down.

In 1988, against West Indies, Dilley was England’s leading wicket-taker, with 15 at 26.86, and on one glorious morning at Lord’s bowled unchanged through the opening session for 13-4-35-4; he would have had five had Derek Pringle not dropped Gus Logie at slip. But after playing twice against Australia the following summer, he joined the Gatting-led rebel tour of South Africa, in effect bringing to an end his international career.

Dilley held a number of coaching roles after his retirement

Dilley held a number of coaching roles after his retirement

Financially, he had long regretted a decision not to join Geoff Boycott’s rebel tour in 1982 and, keen not to miss another payday, had helped Gatting’s recruitment drive. Discontent with his salary at Kent had been instrumental in his move to Worcestershire and, although it was the acquisition of Botham that dominated the headlines, Dilley proved a key component in the county’s run of success. In 1988, when they won the title for the first time in 14 years, he took 34 wickets in nine Championship games and, when the pennant was retained the following summer, he contributed 55. Captain Phil Neale remembered Dilley approaching him to discuss the key fixtures for the remainder of the season. “He was always reading the game and working out when I might need him to bowl,” Neale said.

Dilley retired in 1992 and, before going to Loughborough, held a number of coaching appointments, including a brief spell as England fast-bowling coach, when he worked profitably with Andrew Flintoff – one of a large number of former colleagues who attended a memorial service at Worcester Cathedral. His coaching career was also recognised by a posthumous lifetime-achievement honour at the UK Coaching Awards, two months after his death.