As the headlines that followed his recent knighthood showed, Geoffrey Boycott remains one of the most controversial as well as one of the most recognisable figures in the game. This superb portrait followed his retirement and appeared in the 1988 Wisden.

Read more from the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack archive

Geoffrey Boycott, an egocentric right-handed batsman of great defensive skills and an occasional in-swing bowler, will be remembered as much for his prodigious scoring record as for his impact, over 25 years, perhaps more, on the history of the Yorkshire county club. He has a facility for making enemies much faster than he made his runs, admits to very few friends, yet inspires a loyalty among his admirers that all politicians must envy.

👑 Sir Andrew Strauss

👑 Sir Geoffrey BoycottA massive congratulations to two England cricket legends who have been awarded knighthoods. pic.twitter.com/JZitUOiU9n

— England Cricket (@englandcricket) September 10, 2019

As a cricketer, a batsman converted to opening in his early days with Yorkshire, he had no peers in England during his career. Abroad, only Sunil Gavaskar, the man who overtook Boycott’s aggregate of Test-match runs, could be compared in application, dedication, attention to detail, tactical acumen, patience and endurance. Even Boycott’s critics would agree, too, that his runs were made often in far more difficult circumstances, in English conditions and on English pitches, than Gavaskar’s. In batting on seaming or turning pitches, or when the ball cut or swung, Boycott for more than twenty years reigned supreme in the world.

This ability to score runs, albeit slowly, when all around him were grateful merely to survive, indicated that Boycott was far from limited in his strokeplay. All the shots were there, but only rarely was the full armoury uncovered; when he did settle upon an attacking innings, however, the ensuing firework display could be a brilliant memory. Three occasions come to mind, the first a brief burst at Bradford in 1977, when Yorkshire were chasing runs on the third afternoon against Northamptonshire and Boycott, astonishingly, was charging from his crease to lift the bowling straight. There was a humid Sunday afternoon at Worcester, where Boycott produced a dazzling 60 at a rate not even Milburn would have scorned.

But the outstanding recollection of Boycott in this mood must be of a World Series Cup match against Australia at Sydney during the 1979/80 tour under Mike Brearley. There had been speculation that Boycott might be dropped from the limited-overs side. Brearley, like every other captain, had his difficulties with Boycott, yet their relationship was only occasionally strained; and Brearley was able, as he was with most players, to inspire some remarkable performances.

On December 11, Boycott walked out with Derek Randall and, against an attack featuring Lillee, Thomson and Walker, scored 105 off 124 balls, including seven fours. He reduced a rowdy Hill, primed to jeer him, to a respectful silence. Englishmen, by and large, are not disposed to embrace Geoffrey Boycott, but that was one time when he induced considerable emotion among the stiff upper lips.

The more customary Boycott, and the experience of batting with him, was summed up thus by a younger contemporary. You were always conscious that you were on your own, in that he was one partner unlikely to surrender his wicket to save you and that you were his partner on his terms. That accepted, there was a lot to learn because his mind, computer-like, was always working.

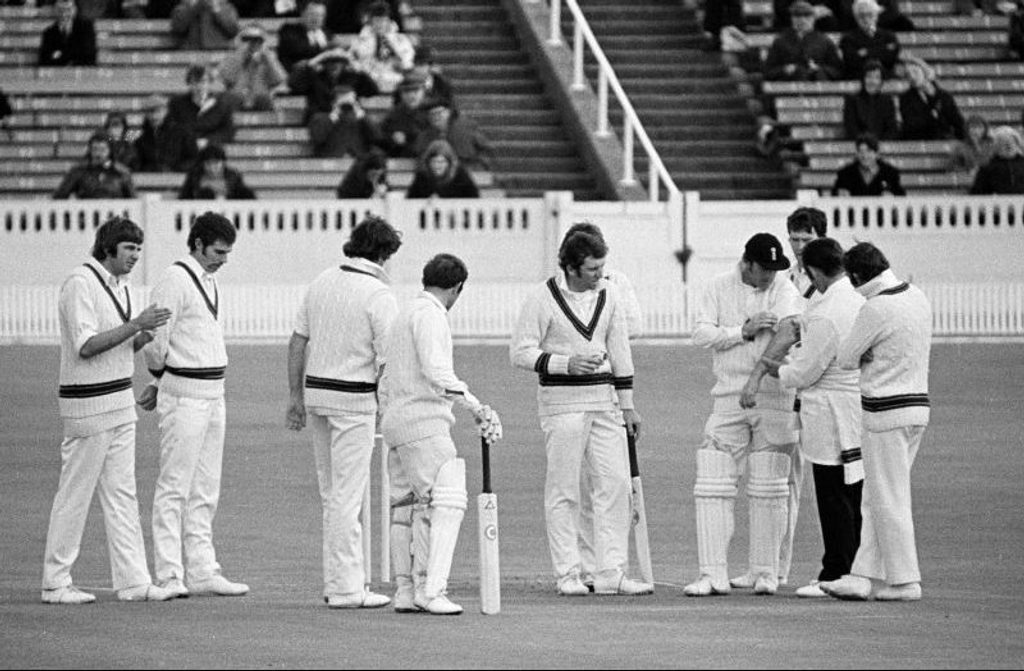

Umpire Charlie Elliot examines Geoffrey Boycott’s arm after he’d been struck by a Dennis Lillee delivery

Umpire Charlie Elliot examines Geoffrey Boycott’s arm after he’d been struck by a Dennis Lillee delivery

He would know who was to bowl and which end they would choose and why. He would anticipate bowling and fielding changes, calculating when and for what reason. He knew most bowlers backwards, most pitches, even the direction of the prevailing wind. You would always know when there was something he didn’t like about one particular bowler when you found yourself with more of the strike than normal. Professionally he was a paragon, immaculate in his preparation and turn-out, and for all the jokes it was an education to stand at the other end and watch him play.

Bradman apart, it is hard to imagine a stronger-minded cricketer in the history of the game. He entered the Yorkshire dressing-room in 1962 and, with his short hair and rimless glasses, was regarded as a rather dull, painstaking young man from South Yorkshire who was unlikely to challenge the obvious rising stars, John Hampshire and Philip Sharpe among them. He was a mediocre fielder, and if anyone knew that he could bowl, his prowess remained a secret. Yet Boycott’s will to succeed was so enormous that he swept into the Yorkshire and England teams with hardly a pause. He had achieved world class when political wranglings inside Yorkshire propelled him on to a larger stage.

By a process of mismanagement that would have brought courts-martial in another sphere, the Yorkshire committee allowed, from the sacking of Johnny Wardle in 1958 to the dismissal of Brian Close in 1970, almost a full Test match team to be dispersed. They preferred Boycott for the captaincy above two, possibly three, more experienced candidates; and then it was that the essential dichotomy in Boycott’s character was fully revealed. How could a man so dedicated to personal accomplishment subordinate his own ambitions to the well-being of a team, and a young team at that, saddled with insecurities and the ever-present knowledge that they were forever being compared with their mighty predecessors?

Other counties were opening their ranks to world-class players from overseas, making Yorkshire’s task of competing doubly hard. Even the traditional reservoir of Yorkshire-born talent began to dry up as the leagues went over to limited-overs cricket. No Yorkshire captain, not Lord Hawke, nor Sellers nor Close, could have conjured up a Championship-winning team in those circumstances.

In a frustrating, difficult time, Boycott was the one link with a glorious past, the still unqualified success in an ever-gloomier world for the Yorkshire follower and member. Not surprisingly, he came to loom larger in the minds of the public, and of many Yorkshire members, than any officer of the club or any other player. Who were these little men who dared criticise the hero?

Boycott also found his international career in a cul-de-sac. What would have been a normal, acceptable and expected progress to the captaincy became complicated when he withdrew from consideration for selection in the mid-1970s mainly, it was alleged, because the England captaincy had not been offered when he expected it. When the crown became available, through Brearley’s injury, in Pakistan and New Zealand in 1977-78, Boycott’s leadership was not received well either by his hosts or his players.

Geoffrey Boycott scored 8,114 runs from 108 Tests at a healthy average of 47.73

Geoffrey Boycott scored 8,114 runs from 108 Tests at a healthy average of 47.73

His international career ended during the Calcutta Test of England’s 1981/82 tour of India. He did not take the field on the final day of that match and returned home shortly afterwards on medical grounds. Memoirs published since, however, alleged that he was sent back as a disciplinary measure. He returned to domestic cricket, passing Yorkshire county records season by season until, in September 1986, the club brought his long career with them to an end by not offering a new contract. He remained, nevertheless, a member of the club’s General Committee.

In 1987, Geoffrey Boycott published an autobiography, reviewers generally regarding it as a long, somewhat tedious attempt at self-justification. A sad book was an almost universal comment, a wry reflection on Boycott’s own influence on the publication for his helper, Terry Brindle, is one of the most humorous of cricket writers. Nor is Boycott himself without humour, taking and giving the dressing-room horseplay with some relish. But he could also, in his time as Yorkshire’s captain, make the dressing-room feared, almost hated, by young Yorkshire players.

So the paradox continues. Once asked to name his closest friend, he could not find one he was confident enough to nominate. Abominated by great Yorkshire contemporaries, he was found by many outside the game to be utterly charming.

Perhaps he was unfortunate to be born in an age when the public interest is served by a media intent upon prying and prising loose every single item, good but preferably bad. Had he lived in Victorian times he might have been regarded as one of the great eccentrics; an intensely private man is a phrase that might have been used. He would not have needed to appear continually before the cameras, the notebooks and the tape-recorders. Grace, MacLaren and Hawke never needed, nor were expected, to justify themselves. His resentment at the poking and probing into his manners, mores and style of life is understandable. A boy born into the South Yorkshire coalfield at any time in the last 50 years came into the world impressed with the need to retaliate first.

Sir Geoffrey Boycott is one of the most recognised voices in cricket

Sir Geoffrey Boycott is one of the most recognised voices in cricket

All over the world Boycott will be remembered for his batting: the ritual, almost fussy re-preparation before each ball, the tap of the bat, touch of the cap, reassurance that his pads were in place, and the relentless, straight-down-the-line forward push. Most of his runs came on the off side because that was where most bowlers bowled to him. The drive through cover, or extra, was minted silver. He was not less adept on the leg side, merely more circumspect, as if suspecting that the pull, hook or sweep all carried elements of risk. Such was his power and reputation at his peak that for him to be bowled was a major surprise. When an Oxford University bowler achieved that feat, the young man was a back-page sensation for a day.

Boycott’s bowling was typical of the man, almost always of mean length and line with a huge inswerve. He performed some notable little feats for Yorkshire on Sunday afternoons, but his captains knew they had to take him off the moment a batsman began to chance his arm. Boycott was deeply upset if he conceded many runs. He transformed himself from a poor fielder to an excellent boundary runner, with a strong, accurate arm, and from time to time he served his county well at slip. He might have been a great captain but for his notorious blind spots, for no-one disparages his knowledge and understanding of the game.

Yet when his career is fully assessed and settled into the record, early next century, will all his foibles and prejudices matter that much? A batting record that stretches, vast and almost unsurpassable, like a distant view of the Himalayas, must put much pettiness into perspective, leaving all the discord in his wake no more than the odd trickle down a great stone face.