Frank Tyson was the ‘Typhoon’ who blew away Australia in 1954-55. His success was brief but he remains among England’s greatest fast bowlers. His Wisden obituary in 2016 revisited an unusual career.

Frank Tyson was the ‘Typhoon’ who blew away Australia in 1954-55. His success was brief but he remains among England’s greatest fast bowlers. His Wisden obituary in 2016 revisited an unusual career.

Long before the name Tyson became associated with heavyweight boxing, it struck terror in the heart of Australians. Frank Tyson reached his fast-bowling peak for just two Tests in the space of three weeks over Christmas and New Year 1954-55. But what a peak it was: 19 wickets to give England come-from-behind wins at Sydney and Melbourne, and set up Len Hutton’s team for one of the most resonant of all Ashes victories. And, though his descent was unexpectedly rapid and his subsequent career anticlimactic, his place in the pantheon was never disputed. Everyone who saw him on that tour, and in flashes of ferocity before and after, recognised him as one of the quickest of all time.

Tyson came from Middleton outside Manchester and learned to play on rough wasteland near his home. Lancashire rejected him after an ill-starred trial in which he turned up late because of a rail strike, then pulled a muscle. In any case, he was distracted by national service and making his way from grammar school to Durham University. However, Northamptonshire’s Australian import, Jock Livingston, happened to play against him in a game in Staffordshire, made a not-exactly-legal approach, and reeled him in. Obliged to sit out the Championship for two years, Tyson bowled his opening first-class over against the 1952 Indians: the first ball swung so much it was taken by first slip; the next four were breathtakingly fast; the sixth had Pankaj Roy caught behind.

Frank Tyson photographed at Northampton station before the 1954-55 Australia tour

Frank Tyson photographed at Northampton station before the 1954-55 Australia tour

He took no more wickets in the game, and did not reappear for nearly a year. But word was out, and it got louder the second time, because the opponents were Australians and the Saturday crowd was around 14,000, the biggest in Northamptonshire’s history. Running in almost from the sightscreen, and with the wicketkeeper, Keith Andrew, standing almost as far back, Tyson had two wickets in his first over: Colin McDonald hobbled off lbw, having been hit inside the pad; Graeme Hole was bowled with his bat still in mid-air. The moment passed – Australia won in two days – but again the memory lingered.

Tyson was available for the Championship after that, and continued to unnerve top batsmen in short bursts. In 1954, he was mentioned as a possible candidate for the winter Ashes, despite concerns he lacked stamina and control. The matter appears to have been settled when Northamptonshire played Middlesex at Lord’s, and Tyson sent Bill Edrich to hospital with a blow on the head. Tyson helped him into the Pavilion but, when Edrich returned next morning, swollen and bandaged, he was greeted with another short one which hit him above the heart.

When this story reached the unsqueamish Hutton, it is said to have made him think this was precisely the sort of bowler he wanted. A week later the squad for Australia was named, with two surprises: Tyson, who edged out Fred Trueman, and Andrew, his county team-mate.

The announcement was made before the Oval Test against Pakistan, when England complacently fielded a weakened team, and lost. But Tyson made a good impression with four for 35 on the opening day. He and Andrew went off to Australia, armed with their cine cameras like wide-eyed schoolboys. They both suffered with the others when England were mashed at Brisbane. Andrew, who had deputised for a sickly Godfrey Evans, would not be given another Test for nearly nine years; but Tyson was not blamed and, when he took six for 68 against Victoria, Hutton had renewed confidence that he possessed a lethal weapon. He used him only in brief spells; Tyson, with help from Alf Gover, who was covering the tour as a journalist, cut down his run and concentrated on yorkers, not bouncers, which was his inclination anyway.

Come the Sydney Test, there was a bonus: Tyson got cross. No mug with the bat, and in at No.7 ahead of the out-of-form Evans, he was hit by a bouncer from Ray Lindwall and rendered briefly unconscious. At 72-2 on the fourth evening, chasing 223, Australia were on top. But Andrew always said his mate bowled better when angry. In his second over next morning, Tyson yorked Jim Burke and Graeme Hole; later he held on – just – to a swirling catch to get Richie Benaud off Bob Appleyard, and soon the score was 145-9, with the last man Bill Johnston joining Neil Harvey, who was in majestic form. Harvey nursed the strike, and both Tyson and his partner Brian Statham were fading. The score crept upwards until, at last, Tyson had Johnston facing at the start of an over. There was a leg-side glance to Evans: England won by 38 runs, the series all-square, Tyson 6-85 and 10-130 in the match. A star was born: “Typhoon” Tyson. Two days later he made a Christmas Eve pilgrimage to Harold Larwood’s house in the suburbs. “When you’ve got 50,000 Aussies shouting at you,” his great predecessor told him, “you know you’ve got ‘em worried.”

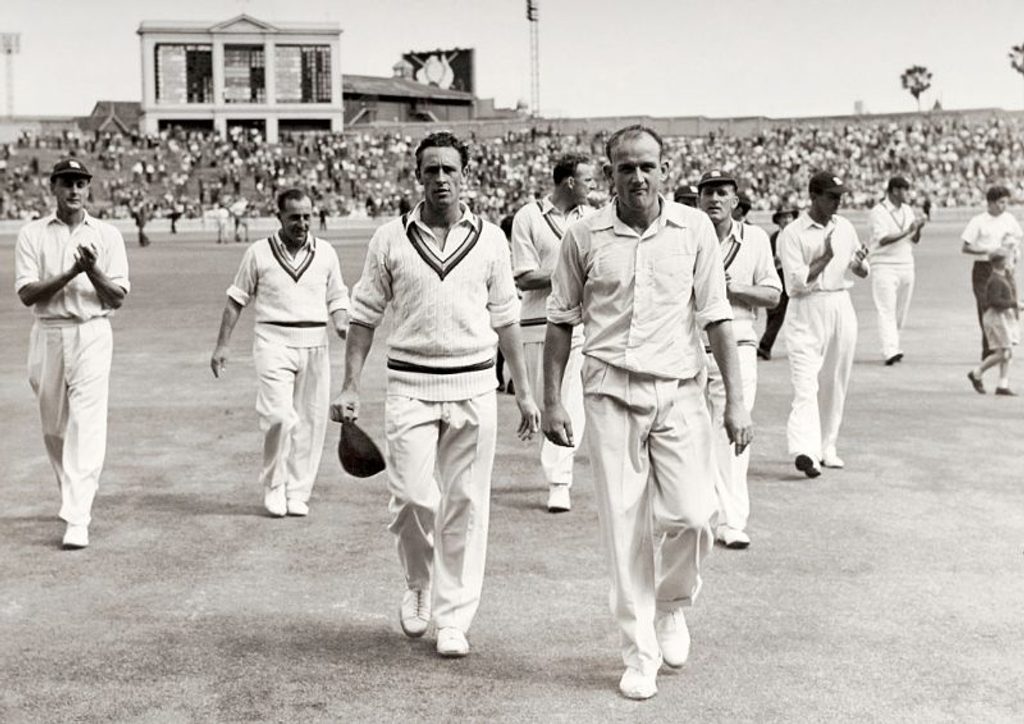

England’s Frank Tyson (right) leading his team off the field after their 38-run win over Australia in the Sydney Test in 1954

England’s Frank Tyson (right) leading his team off the field after their 38-run win over Australia in the Sydney Test in 1954

The Melbourne Test began on New Year’s Eve. The pitch was difficult but England, 40 behind on first innings, set a target of 240. Again Australia started the final morning hopefully, at 75-2. But this time there was less tension, and Tyson was even more irresistible: 7-27, victims of pace, control and, when necessary, cunning. He was a vital, if less spectacular, contributor in Adelaide, where England clinched the series, and was later far too hot for New Zealand to handle (11-90 in the two Tests).

But, the world being a bigger place in those days, he was largely insulated from the response back home. “You think you’ve bowled reasonably well,” he reflected from retirement. “When, three months later, you get off an aircraft and there are 50 pressmen to meet you, you think ‘What have I done?’”

And for a while, the wickets kept coming at the same rate: 7-44 against Worcestershire on his hero’s return to Northampton in May 1955; and 6-28 in the second innings of the opening Test against South Africa, including a final blast of 5-5. He was one of Wisden’s Five Cricketers of the Year. But, despite a handful of triumphs, the rest of his career lacked the earlier drama.

Frank Tyson represented England in 17 Tests between 1954 and 1959, claiming 76 wickets at 18.56

Frank Tyson represented England in 17 Tests between 1954 and 1959, claiming 76 wickets at 18.56

Tyson believed (as Hutton did) that he was ruined by the Northampton pitches, prepared to suit their array of spinners. But he also became susceptible to injuries. He was chosen for the 1956-57 tour of South Africa, and for the disastrous return to Australia in 1958-59, but was applauded from a Test match field only once more, when he took six for 40 in the second innings at Port Elizabeth, on a shocking pitch and in a losing cause. He still had his moments in county cricket too, notably when he destroyed Glamorgan with seven for 25 at the Arms Park in 1957 – backing up Andrew’s theory about making him angry: someone had snipped his tie in half as a prank. That was the only year he took 100 wickets.

Having a degree in English literature, Tyson was, for his era, a most unusual professional. And he had other ambitions. He retired in 1960 and taught for a while in Northampton before taking the Larwood route to Australia, along with his Aussie wife Ursula. Unlike Larwood, he had no animosity to overcome: he had never attracted controversy. And he was a thoughtful, affable and kindly man. He taught at Carey Grammar School in Melbourne, nurturing scholars in English, French and history, as well as cricketers like Graham Yallop. In 1975 he became Victoria’s first coaching director, staying for 12 years before retiring to the Gold Coast. Between whiles, he was a skilful and sympathetic cricket broadcaster. He wrote well, producing a succession of books including, in 2004, the charming diary he had quietly written 50 years earlier during the time of his life. In retirement, he took up oil painting.

Tyson was not a big drinker, but he was one of those men on whom a little had a remarkable effect. In 1978 the teenage Jonathan Agnew was sent to Australia on a fast-bowling scholarship and billeted with the Tysons. After barely a sniff of beer, Agnew recalled, the amiability would suddenly vanish. “You think yer a fast bowler, do yer?” he would roar and rush out into the garden. “He’d roll up his sleeves and be racing round the garden, bowling the ball into the hedgerows and goodness knows where else, like a man possessed.”

Tyson, Frank Holmes, died on September 27, 2015 aged 85.