In the golden year of 1953, England won back the Ashes for the first time since before the Second World War. In the 2003 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, Steven Lynch recalled a summer to savour.

Read more features from the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack

Previous Almanack feature: Banished to Boothill: A tribute to short leg – Almanack

There was something special about 1953. In England, things were finally looking up after the grim war years and the struggle to put matters on an even keel afterwards. Rationing was on the way out, it was no longer obligatory to wear a hat in public at all times, and pop charts and flighty fashions were tiptoeing their way in. The mood was epitomised by a youthful new sovereign – the youngest since Victoria in 1837. Queen Elizabeth II, aged 25 on her accession, was crowned at Westminster Abbey on June 2, 1953. Within a month she was meeting 22 of her subjects, English and Australian, in front of the Lord’s pavilion.

In an age of uncomplicated national pride, there were plenty of reasons to be proud of Britain. The day before the Coronation it was announced that a British-led expedition had become the first to climb Everest. At Epsom, Gordon Richards, the master jockey, won the Derby at his 27th attempt. At Wembley, Stanley Matthews jinked his way to an FA Cup-winner’s medal at last, in a classic final. At Cambridge, Francis Crick and James Watson were breaking the code of human life with their paper on DNA.

A summer of pride – Stanley Matthews (left) finally achieved FA Cup glory

A summer of pride – Stanley Matthews (left) finally achieved FA Cup glory

Some things don’t change, though. An American won Wimbledon – Vic Seixas, whose movie-star looks won him almost as many fans as his cross-court volleys won rallies. Then, as now, England hadn’t held the Ashes for a dismally long time – 19 years – and as usual these days the only Test they won against Australia in 1953 was the fifth and final one. But since England had taken the precaution of drawing the previous four games, this was cause for celebration rather than consolation. The Ashes, surrendered in 1934 in the series after Bodyline, were back home at last. England would remain on top of the Test tree for most of the 1950s.

And for the first time ever, large numbers of their supporters would be able to see them in action. The 1953 Ashes were the first Test series watched by a significant number of people on television. The first TVs were very expensive and largely confined to rich homes, but many British households splashed out on their first set in 1953 to watch the Coronation (in Australia, the explosion had to wait a little longer, for the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne). In the nation’s great love affair with the television, 1953 was the first date. Apparently my aunts and uncles, and most of the neighbours too, sat down to watch the Queen being crowned on the sparkling new set with its giant wooden cabinet and tiny grey screen. My grandfather had bought it at a knockdown price from the Ideal Home Exhibition, where he was working at the time.

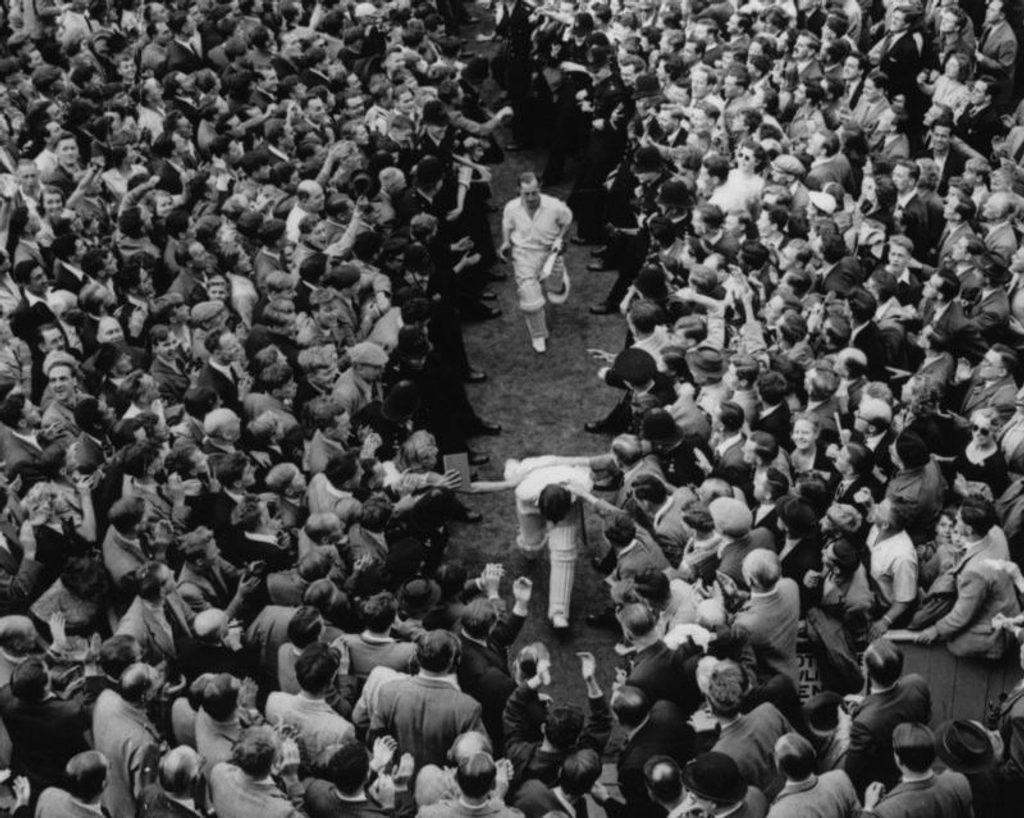

A huge crowd gathered to witness England’s victory at The Oval

A huge crowd gathered to witness England’s victory at The Oval

And after all the pageantry and panoply, and in between potter’s-wheel interludes and playful-kitten intermissions, ordinary people sat spellbound at the exploits of Hutton and Bedser, Lindwall and Miller, Bailey and Watson. It was such early days in the relationship between the game and the screen that players barely noticed. “I wasn’t conscious of that,” says Trevor Bailey, England’s key all-rounder in that series and many more in the 1950s. “To a degree there was more recognition, yes, but I put it down to everyone being so interested in the series. This was England not long after the war, remember – there weren’t many other distractions, and cricket was very popular. On the last day at The Oval there was a big and enthusiastic crowd.”

Fred Trueman, called up for the first of many jousts with the Aussies for the decider at The Oval, also has vivid memories of that far-off finale. He told Wisden Cricket Monthly in 2003: “On the fourth morning we needed 94 to win. I came down to the ground from the Great Western at Paddington with Leonard [Hutton, the England captain]. Outside there was already an excited throng, and I remember like it was yesterday seeing across the road a newspaper placard with a picture of the urn and in great big type the simple three words, ‘LEN – THEY’RE OURS!’”

“It was the most satisfactory game I’d ever played in,” says Bailey, who turns 80 at the end of 2003 but retains the snappy, decisive bark that characterised his radio summaries for Test Match Special. “But it was a very close series, an intriguing battle. We had the better of two draws, and they had the better of the other two. We should probably have won the First Test and the Third, and they looked likely to win the Second and the Fourth. But there was a lot of rain about.”

Indeed there was. England were well placed in the First Test at Trent Bridge, after Alec Bedser’s 14 wickets had set up a modest target of 229. Hutton, England’s anchor since 1938, was still there, but rain washed out all the fourth day and most of the fifth – and when play did resume, after tea on the final day, there was insufficient time for a result. Peter West wrote of Bedser’s display of medium-fast bowling: “This was the sublime performance in all his glowing career… I can recall his bowling only one bad ball in the whole match.”

At Lord’s, Australia held the upper hand after centuries from their puckish captain, Lindsay Hassett – his second of the series – and Keith Miller, whose flickback of a skein of unruly hair predated Shoaib Akhtar’s by half a century. By the close on the fourth day, England were floundering at 20 for three, chasing 343, and it might have been worse if Ray Lindwall at short leg had clung on to either of two sharp chances from Willie Watson in the last over of the day. Watson survived, and combined with Bailey in an epic final-day stand which lasted more than four hours to deny Australia victory. Bailey, whose previous best against Australia was only 15, made 71 in 257 minutes. “I enjoyed that,” he says with relish. Wisden noted that he played “a deadbat pendulum stroke to every ball on his wicket.” It defined Bailey’s career. A few years earlier, Wisden had called him an attractive strokemaker, but now… “I became known as The Barnacle, with the forward-defensive my signature tune.”

That partnership remained Watson’s finest hour. A slight left–hander from Yorkshire, he would be acclaimed these days as a sporting superstar – he also played football for England, and had been in the squad for the 1950 World Cup, when England famously lost to the United States, but didn’t actually play. Long after, he would remember going up to Bailey during their stand and asking whether they should go for the runs; 343, in those days, was unthinkable unless you had Bradman in your team. “Trevor just turned his back on me and walked away.” Watson seemed set for a long run in the side, but England’s selectors, then as now, could be capricious: he fell from favour before the end of the series, and was not at The Oval to see the victory he had made possible.

Trevor Bailey (right) was England’s key all-rounder in the series

Trevor Bailey (right) was England’s key all-rounder in the series

England were back on top in the Third Test at Old Trafford, and this time it was the Australians’ turn to be saved by the rain. When Neil Harvey was bothered by water on the knee, Brian Johnston observed that it was hardly surprising. The total playing time was restricted to a shade under 14 hours, but the last part was action-packed. Johnny Wardle, bowling the left–arm chinamen that his county, Yorkshire, frowned upon as too frivolous for Championship cricket, reduced Australia to 35 for eight before time ran out.

England managed only 142 off 96 overs on the first day of the Fourth Test at Headingley, watched by those Bodyline rivals Don Bradman and Douglas Jardine, sitting “cheek by jowl” in the press box, according to Jack Fingleton in his excellent book The Ashes Crown the Year. Australia grabbed the upper hand with a lead of 99, but again ran into a stone wall named Bailey. This time he made 38 in 262 minutes. “We were fighting hard to save the game again,” Bailey remembers. “I was in with Jim Laker, and two minutes before lunch I called him over and said I was going to appeal against the light. He said ‘But the sun’s out,’ and that’s what the umpires said too – but by the time they’d talked about it, there wasn’t time for another over and we all trooped off for lunch.”

As if his innings wasn’t enough, Bailey deliberately bowled down the leg side as Australia vainly chased a target of 177 in 115 minutes. This ensured it was all square going into the final Test, which was extended to six days to maximise the chances of a result.

At The Oval, Bedser pounded in for three more wickets, to take his series tally to an amazing 39, most of them greeted by a handshake, a hitch of his heavy flannels, and a hike back to the mark to prepare for the next victim. That walk was child’s play for a man used to a twice-daily trudge of over a mile between his home and Woking station for the train-ride to The Oval.

Alec Bedser (centre) collected an almighty 39 wickets across five Tests

Alec Bedser (centre) collected an almighty 39 wickets across five Tests

Hutton and Bailey ground out a narrow lead before Jim Laker and Tony Lock, on their home turf, bowled Australia out for 162. It wouldn’t have been as many but for a robust 49 from Ron Archer, one of a trio of young all-rounders in the Australian party. Richie Benaud and Alan Davidson were the others, and are better remembered now, but Archer was equally promising. Tall and strong, he was only 19 in 1953, but the glittering career that beckoned was restricted to 19 Tests by back trouble and a serious knee injury.

England were left needing 132 to regain the Ashes – just enough to enable a hiccough or two. There was about an hour’s play remaining on the third day, and England lost Hutton to an unnecessary run-out – John Arlott recalled that it was “an added anxiety” for a tense crowd. “The prospect of winning the Ashes after 19 years has been so distant,” he said, “that we have become like some small boy who has looked forward to a special treat for so long that he fears something will happen to stop it – or is himself sick with excitement so that he cannot enjoy it.” But next day England made light of the target, eventually reaching it at 2.55. The last couple of balls became some of the most-screened film in cricket – for years the BBC used the footage of Denis Compton pulling Arthur Morris to the boundary for its trade-test transmissions, complete with an ecstatic Brian Johnston yelling “It’s the Ashes!”

Denis Compton and Bill Edrich make their way through the crowd after England’s win

Denis Compton and Bill Edrich make their way through the crowd after England’s win

The crowds were huge, and expectant – and they went away happy in the end. But, as Bailey argues, “I’ve always thought that if Hassett had gambled and put us in at The Oval then they might have won. But he batted instead, and the ball moved about a bit on the first day, then it turned later on. They had left both of their spinners out, but we had Laker and Lock. Actually I always had my doubts about Hassett as a tactician. His players adored him – he was one of the boys, whereas his predecessor Don Bradman was of a different generation – but tactically he wasn’t as strong or as sharp as Bradman. Bradman was especially good after the war, I think. He was still scoring an awful lot of runs, and he was like a god to the younger players. In 1948, England were short of fast bowlers and I thought I had a chance. I was at Cambridge University at the time but I went down specially to play for Essex against the Australians in May. That was the day they made 721 at Southend – and it was then I realised that I was never going to be an out-and-out fast bowler, not once I’d seen people like Lindwall and Miller. I did get Bradman out once, though. It was a long-hop, as I recall.”

England’s XI from The Oval in 1953 has a good claim to being their best ever. Stuffed with all–time greats, the side was Len Hutton, Bill Edrich, Tom Graveney, Denis Compton, Peter May, Trevor Bailey, Godfrey Evans, Jim Laker, Alec Bedser, Tony Lock and Fred Trueman, with Johnny Wardle huffing and puffing about the indignity of being made twelfth man.

They not only had formidable Test careers but remained closely involved with cricket long after retiring. There were no forgotten men as there are in most teams, such as their opponents (remember Graeme Hole, or Jim de Courcy?) and the Ray Wilsons and Roger Hunts of England’s 1966 football World Cup winners. Bedser and May both became chairman of the Test selectors, and Hutton was a selector too for a time. Compton juggled a chaotic life of commentaries, endorsements and missed engagements – often with his lifelong soulmate Edrich. Laker added northern nous to the television commentary box, along with an inability to pronounce the “g” in words like “batting” and “innings” that drove retired schoolmasters in Eastbourne to distraction. Graveney also had a longish career at the microphone with his catchphrase “really speaking”. Bailey and Trueman were trenchant radio summarisers for years, stressing the need for line and length to generations of cricket-lovers. Lock moved to Australia to prolong his playing career, led Western Australia to the Sheffield Shield title, and became a coach there. Evans, complete with improbably large sideburns, set the cricket odds for bookmakers in the days before that assumed sinister overtones.

John Woodcock, the veteran Times correspondent and former Wisden editor, is better placed than most to comment on just how exceptional this team was. “It was certainly as good a side as England have fielded in my time,” he says. “It’s a better team than those that won the Ashes in Australia in 1970-71 and 1986-87, and as well balanced as the one that won in 1954-55. The side that won easily in Australia in 1928-29 was obviously a very good one, and there’s always talk of the team from 1902 that had 11 century-makers in it – but even I’m not old enough to have seen them. Comparisons between different eras are awfully difficult, but you have to go by how many great players there are in each team, and there were plenty in that 1953 side.”

Bailey is inclined to agree. “By 1953 Bradman had retired, and although Australia still had probably the better team, there wasn’t much in it. We had Hutton and Compton, who were world–class batsmen, a world-class medium-pacer in Bedser, and Evans was the best wicketkeeper around. We had Laker and Lock, who were a real handful on a dodgy pitch, and young batsmen like May and Graveney. For the final Test of 1953 we also had a genuine fast bowler in Fred, who was certainly a lot quicker than Alec and myself. We had a good side, we were just coming to the top – and we stayed there until the end of the 1950s.”

It wasn’t all praise, though. Hutton’s reign as captain is remembered now for slow scoring, and over-rates that were considered funereal for the time. England may have achieved world domination for the rest of the decade, but they were often unappetising to watch. Freddie Brown, chairman of selectors in 1953, took the unusual step of attacking his own team: in the following year’s Wisden, he wrote that he had found “an almost unanimous disquiet about the lack of attack in the England batting”. Brown pointed out that England had scored at 33 runs per 100 balls in the series, as against Australia’s 44. The difference was most marked in the Fourth Test at Headingley, where England, trying to save the game, pottered about at a strike-rate of 24 to Australia’s 56. However, Woodcock isn’t sure about the near-unanimity: “I don’t remember too much fuss being made at the time. If England batted slowly, which I dare say they did at times, it was because it was important that they did so in order to win, and I think they can be forgiven for that.”

The slow batting, and all the rain, mean that 1953 cannot be ranked as the best Ashes series of them all. That remains a toss-up between 1894–95, 1902 and 1981. But this one did signal a shift in power, from Australia to England, and defined the style of the decade. There were more soggy draws than rumbustious run-chases.

Bailey is unequivocal. “Nobody seemed terribly bothered about it at the time. We were winning. We got the result, that’s what it was all about.”