Denis Compton, one of England’s greatest batsmen and most famous sportsmen, died on April 23, 1997. His Wisden obituary celebrated his life and career.

Compton, Denis Charles Scott, CBE died on April 23, 1997, aged 78.

This article was first published in the 1998 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack. See more from the Almanack archive.

Denis Compton was not just a great cricketer but a character who transcended the game and became what would now be called a national icon. In the years after the war, when the British were still finding the joys of victory elusive, the exuberance of Compton’s batting and personality became a symbol of national renewal. Almost single-handed (though his pal Bill Edrich helped), he ensured that cricket returned to its pre-war place in the nation’s affections. Only Ian Botham has ever come remotely close to matching this achievement.

Compton was a remarkable batsman: loose-limbed with broad shoulders and powerful forearms. He could play all the strokes, though he rarely straight-drove. What made him special was his audacity: he would take risks, standing outside the crease even to quickish bowlers, challenging them to bowl anything other than the length he wanted. He took 622 wickets, mostly with his chinamen, and any other player might have turned this skill into a career; Compton regarded them as a bit of a party trick. His running between the wickets was never good, but it seemed to get worse after he retired and became the source of a thousand after-dinner jokes. In reality, it was never a disastrous weakness.

Compton batting for England against South Africa, 1947

Compton batting for England against South Africa, 1947

Denis Compton was born in Hendon, on May 23, 1918, and described his childhood as both “poorish” and “happy”. His father was a self-employed decorator who became a lorry driver when his business floundered. He was also a keen cricketer, as was Leslie, Denis’s elder brother. They played against the lamp-posts in Alexandra Road and at Bell Lane Elementary School, and Compton’s talent was obvious at once. At 12, he was playing for his father’s team, and North London Schools against South London Schools at Lord’s. He made 88. Two years later, watched by Sir Pelham Warner, he made 114 at Lord’s for the Elementary Schools against C. F. Tufnell’s XI and led his team to a crushing victory.

He joined the Lord’s staff in 1933, and three years later got a game for the county, as an 18-year-old against Sussex in the Whitsun match. Compton batted at No. 11: he scored 14 in an important last-wicket stand with Gubby Allen that gave Middlesex first-innings points; the umpire Bill Bestwick supposedly said later that he only gave Compton lbw because he was desperate for a pee.

Next match he was No. 8 and facing Larwood with confidence. Then he was No. 7, scoring 87 against Northamptonshire. In one game, the captain Walter Robins came down the pitch after he had driven a fast bowler for two consecutive fours. “You know what to look out for now, don’t you?” “No, skipper.” “Well, he’ll bounce one at you.” “If he does, I shall hook him.” And he did – into the Mound Stand. Before June was out he scored a hundred, in an hour and three-quarters, at Northampton. By the time the season was over and he had passed a thousand runs, Warner, then chairman of the Test selectors, called him “the best young batsman who has come out since Walter Hammond was a boy”.

But Compton had no time to relax. In September he made his Football League debut for Arsenal on the left wing against Derby County, scored the opening goal in a 2-2 draw, and was called “the success of the afternoon” by the Daily Express. Soon he was being marked out as a future England footballer as well as cricketer, despite criticism, which Compton always accepted, that he was inclined to prefer pretty ball-play to anything else. In cricket, the golden youth’s progress turned out to be stoppable only by the Germans.

Compton’s (right) sporting talent went beyond the cricket field

Compton’s (right) sporting talent went beyond the cricket field

In 1937 he scored 1,980 runs and was picked by England against New Zealand at the Oval. He scored 65 and was run out, flukily, while backing up. That year, as Pasty Hendren retired, Bill Edrich qualified for Middlesex. Len Hutton also made his Test debut. Thus started both the great partnership and the great rivalry that were to dominate post-war cricket. The contrast between the serious-minded Hutton and the insouciant Compton would be the great divide in English cricket for years, and small boys of all ages invariably inclined to one or the other.

Next time Compton batted for England, against Australia at Trent Bridge in 1938, he made 102; then came a match-saving yet exuberant 76 not out at Lord’s. But he contributed just a single when Hutton scored his 364 at The Oval. Compton preferred to play football rather than tour South Africa- the 10-day Test at Durban would not have suited him – but in 1939 was back to top cricketing form, scoring 2,468 runs, including 120 against West Indies at Lord’s, when he put on 248 with Hutton in two hours 20 minutes. There is no telling what this generation of batsmen might have achieved had they not been so rudely interrupted. Possibly, in the absence of equally compelling bowlers, they might have got bored. They never had the chance to find out. Soon Compton was a special constable and then a member of the Royal Artillery, posted first to East Grinstead which still allowed the chance of weekend football. (He won 12 wartime and Victory match football caps for England, which did not officially count, but many contemporaries agreed that he was now the best outside-left in the country.)

In 1944 he was sent to India as a sergeant-major supposedly in charge of getting men fit to defeat Japan; his lenient approach to this task enhanced his popularity with the men, and the Allies still won the war. He was able to fit in 17 first-class matches in India as well. His performances included a century for East Zone against the Australian Services, which was interrupted by rioters for several minutes when he was in the nineties. The line “Mr. Compton, you very good player but the game must stop” became one of the catch-phrases of his friendship with Keith Miller, which ended only with Compton’s death. Compton also appeared, in the casual manner of that era, in the extraordinary Ranji Trophy final of 1944-45, then the highest-scoring match ever, between Holkar and Bombay.

Compton struggled at first in 1946, and his first 12 months of post-war cricket are sometimes thought of as a failure. He was still the leading scorer with 2,403 runs in 1946, and made a hundred in each innings at the Adelaide Test the following February.

Because Compton had been touring, he missed that icy, fuel-rationed winter which for many people in Britain was tougher than anything produced by the war. Thus the stage was set for the greatest cricket season any individual has ever had. Compton did not really hit form until the season was a month old, and did not emerge into his full glory until the sun came out, and the series against South Africa began. He scored 753 of his 3,816 runs that summer in the Tests. But somehow, in the mind’s eye of a generation, he was always batting at Lord’s in a county match: hair tousled, the ball racing past cover point or backward of square.

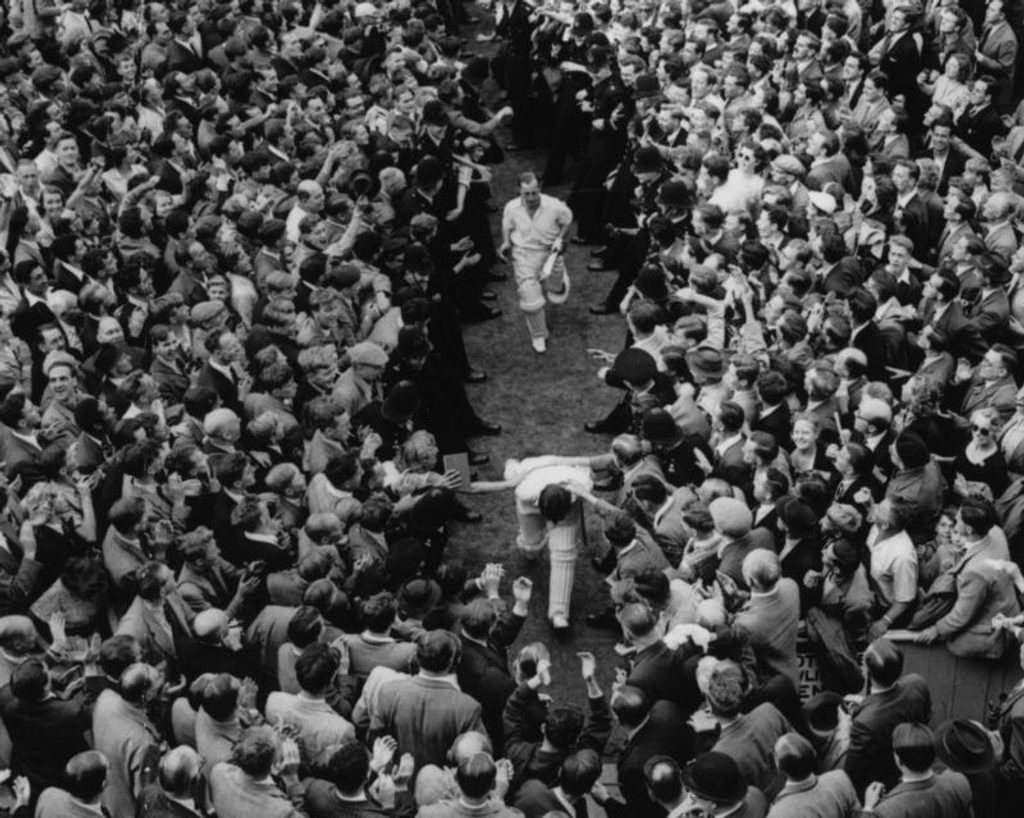

Compton and Bill Edrich make their way through the Oval crowd after England’s 1953 Ashes victory

Compton and Bill Edrich make their way through the Oval crowd after England’s 1953 Ashes victory

An exile in Australia complained: “I hardly expected him to score 18 hundreds in a season. I thought him too good a player for that sort of thing.” He was assured that Compton had just played his natural game and the centuries – like his aggregate, a record for any season – had been almost incidental. Even more incidentally, Compton and Edrich took Middlesex to the Championship. The only cloud in that perfect summer came in the very last county match at Lord’s: Compton had to retire to the pavilion because of knee trouble. He came out to make a second-innings century, another against the South Africans, and a further 246 – the knee strapped – for Middlesex against The Rest at The Oval.

But from then on the words Compton and knee were to go together almost as easily as Compton and Edrich. Apparently, it was first damaged in a collision with Charlton goalkeeper Sid Hobbins in 1938, but it now became increasingly troublesome to him, and a constant source of worry for the public too. There were still many great innings – two big Test hundreds in 1948 against Bradman’s invincible Australians, an astounding 300 in three hours against an admittedly weak North-Eastern Transvaal team a few months later – but they came less certainly. As a cricketer his zenith had been so high that the only possible way was down.

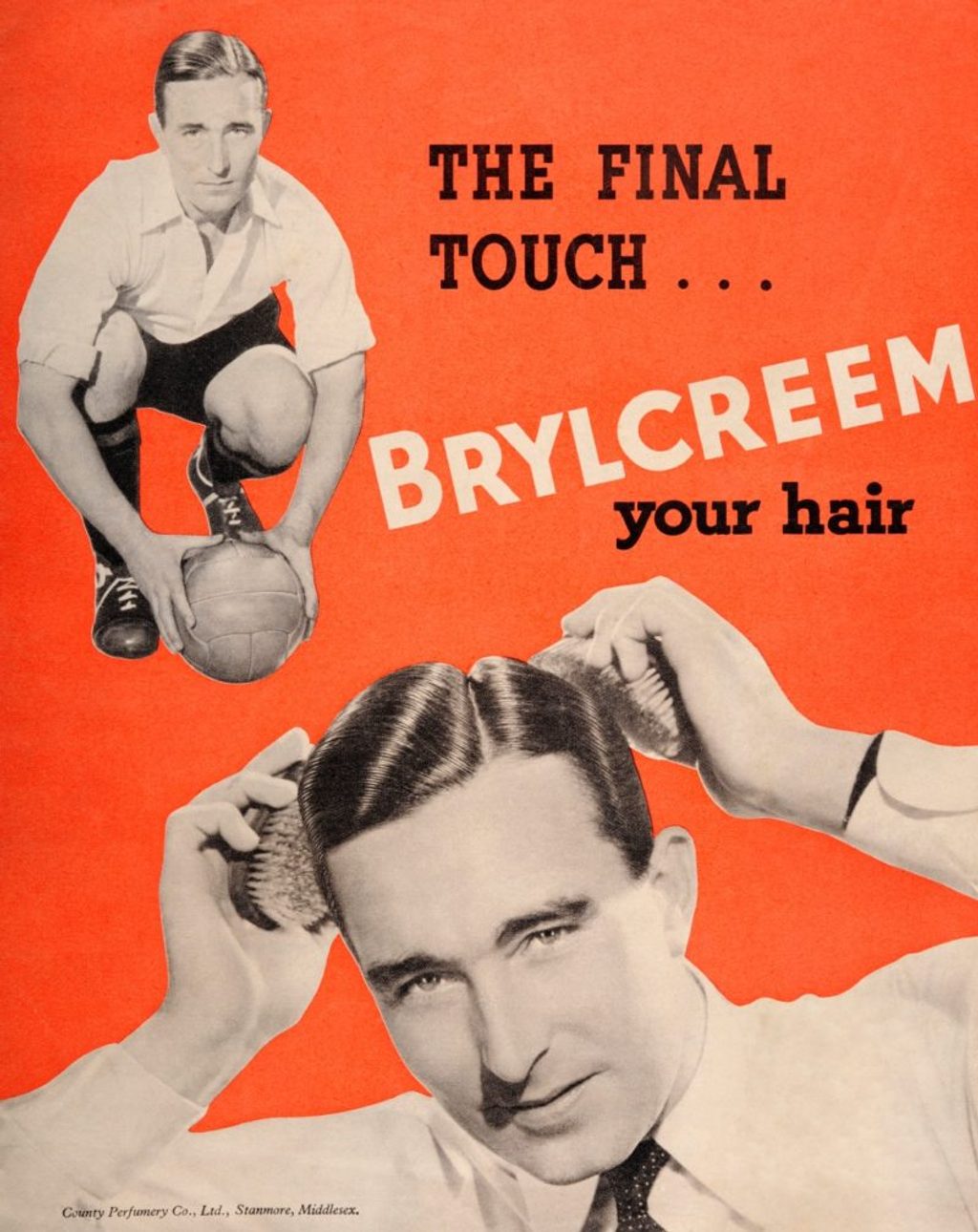

He was, however, now much more than a cricketer. On the 1948-49 tour of South Africa, he approached the journalist Reg Hayter with a suitcase full of unopened letters. Hayter started to go through them and found one from the News of the World offering £2,000 a year for a weekly column. Then he found another, written a few months later, withdrawing the offer because there had been no reply. Hayter introduced Compton to Bagenal Harvey, who became the first sportsman’s agent, and did the famous deal in which Compton slicked down his hair and became forever identified with Brylcreem.

“Compton slicked down his hair and became forever identified with Brylcreem”

“Compton slicked down his hair and became forever identified with Brylcreem”

In the spring of 1950 he was still able to come out of footballing semi-retirement, get into the Arsenal team during their FA Cup run and get a winner’s medal at Wembley, where they beat Liverpool 2-0. But in the Whitsun game against Sussex, his knee gave way and he missed much of that summer. He failed horribly in the Tests in Australia in the winter. In May 1951, after being appointed joint captain of Middlesex with Edrich, he scored 909 runs, more than in May 1947, but Compton’s knee was by now entering national folklore, his appearances were becoming curtailed, and his ambition less intense. The runs still kept coming: he made the hit that won the Ashes in 1953, and in 1954, against Pakistan, there came both his highest Test score, 278 at Trent Bridge, and the innings he was inclined to regard as his best, 53 on a wet pitch at The Oval. He scored 492 in the 1955 Tests against South Africa. That November he had his right kneecap removed; his surgeon kept it as a souvenir, before giving it to MCC as part of the Lord’s archive. Compton’s biographer, Tim Heald, examined it and reported that it was like “a medium-sized mushroom, honey-coloured and honey-combed”.

The operation enabled him to carry on playing for another two seasons, and to tour South Africa in 1956-57. He left county cricket as triumphantly as he entered it, hitting 143 in three hours in his final match as a professional for Middlesex in 1957. Thereafter he made occasional appearances as an amateur, scored his 123rd first-class hundred for the Cavaliers on a sociable trip to Jamaica in January 1964, and finally bowed out with a fifty for MCC against Lancashire later that year.

By then, he had become a thoroughly successful ex-cricketer, commentating for the BBC, writing pieces for the Sunday Express that were usually absurdly optimistic about the talents of iffy young cricketers, and using his natural readiness to have a drink and a chat with anyone to win accounts (successfully) for advertising agencies, first Royds then McCanns. He remained a bit of a roisterer into old age and maintained the friendships of his playing days until death. Edrich and Miller were at the top of this list; but it extended to all the South Africans he had found such chivalrous opponents and generous hosts. This led him to take the pro-white South Africa side in the disputes that followed his retirement and to be used on occasion – such as the 1983 debate over sending an MCC team to South Africa – by those with dubious motives.

He never lost the slightly chaotic ingenuousness that was responsible for the suitcase of letters: he was always unpunctual and would arrive, as Michael Parkinson put it, in a cloud of dust even when he was walking with a stick. His home life was successful only serially, but his third and last wife provided two daughters to add to his earlier families, which helped keep him young. He was always young at heart, even towards the end when the pain from his hip merged with the pain from his knee. He died in hospital at Windsor on St. George’s Day, following complications from his third hip operation. His memorial service at Westminster Abbey created more applications for tickets than any in 30 years. Cricket was hugely fortunate that such a gifted sportsman graced the game with his presence. It was doubly blessed that he was a man of modesty, charm and good nature.