Clive van Ryneveld captained South Africa at cricket and played rugby for England. As his Wisden obituary revealed, there was quite a bit more to his life.

Van Ryneveld, Clive Berrange, died on January 29, 2018, aged 89.

But the 2019 edition of the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack here!

If Clive van Ryneveld had been an international sportsman and nothing else, his career would have been distinguished enough. As a cricketer, he played 19 Tests for South Africa, captaining them in two series, including a famous comeback against England in 1956-57. In rugby, he appeared in the Five Nations for England while at Oxford University, scoring three tries. But sport wasn’t the half of it. As a politician, he helped form a rebel party to oppose apartheid; as a lawyer, he defended black political protesters.

Tall, athletic and languid, van Ryneveld cut a Corinthian figure. He came from a privileged background, but was not blind to the injustices in his homeland. His captaincy was strictly principled. Against Australia at Durban in 1957-58, he refused to run out Neil Harvey after the batsmen stopped, assuming the ball had gone for four. Later in the series, at Port Elizabeth, he withdrew Neil Adcock and Peter Heine from the attack when they ignored his one-bouncer-per-over edict.

Van Ryneveld’s ancestors had arrived in southern Africa in 1759, and quickly became involved in government and administration. (The family house, Groote Schuur, was later the official home of the prime minister.) His father, also Clive, played rugby for South Africa, while Jimmy Blanckenberg, an uncle, took 25 wickets against England in 1922-23. Van Ryneveld attended Cape Town’s Diocesan College, a mile from Newlands: sport mattered, but he also learned the values that were to guide his later work. The master in charge of cricket was Pieter van der Bijl, who made 125 and 97 in the Timeless Test against England at Durban in 1938-39 (van der Bijl’s son, Vintcent, the former Natal and Middlesex fast bowler, was van Ryneveld’s godson). An attractive, predominantly off-side batsman, a brilliant fielder in any position, and an occasionally destructive leg-spinner, van Ryneveld clearly had potential. Aged 18, he made his debut for Western Province against Rhodesia in 1946-47, and hit a match-winning unbeaten 90 in the second innings. Later in 1947, he left Cape Town for Oxford, after earning a Rhodes scholarship to University College.

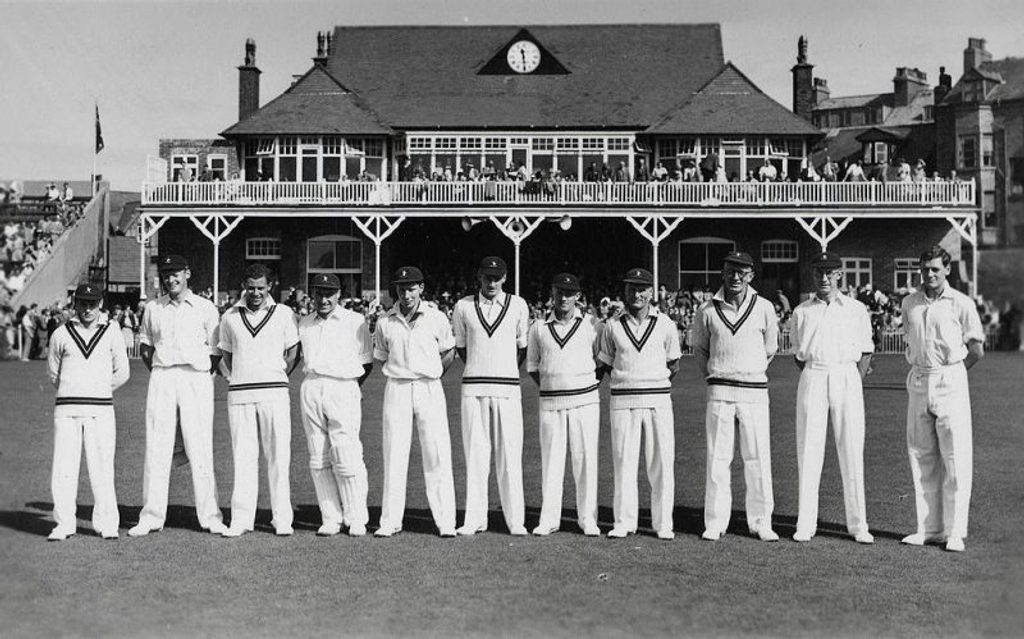

South Africa Cricket Team that toured England for a Test series at the Scarborough Cricket Festival, circa January 1951. CB Van Ryneveld (first from right)

South Africa Cricket Team that toured England for a Test series at the Scarborough Cricket Festival, circa January 1951. CB Van Ryneveld (first from right)

He read law, although the college, said van Ryneveld, was “tolerant of students whose sporting activities were time-consuming”. He went straight into the Oxford XV, appearing in the first of three Varsity Matches (he missed five penalties), and played cricket in 1948, taking on Bradman’s Invincibles – though not Bradman – and claiming seven for 57 as Oxford won the Varsity Match at Lord’s. By tradition, the captain for the following summer was elected after the second day: with the support of the colonial players, van Ryneveld won.

A dashing centre with superb hands and a lethal burst of pace, against Cambridge at Twickenham in December, he ran almost the length of the pitch for a try that entered the fixture’s folklore. He came through England trials for the Five Nations, and played in all four matches. “I don’t think they worried too much about qualifications then,” he said. “I certainly didn’t quibble.” He had to bring his own shorts – and hand back his shirt after each game. Team talks were restricted to a visit from the RFU president: “Tackle hard, chaps.” On his 21st birthday, he scored two tries against Scotland at Twickenham, earning a gentle rebuke from The Times for diving over the line “in the manner of the storybooks”.

He became Oxford cricket captain in 1949, when they beat four counties and the New Zealanders – the tourists’ only defeat of the summer. Van Ryneveld scored a hundred against Worcestershire, and his fielding was electrifying. “He took horizontal catches at mid-on and mid-off that only a rugby player could have taken,” said team-mate Derek Henderson. Wisden praised his “spirited” captaincy. Oxford were strong favourites for the Varsity Match, but lost by seven wickets. Selected for the Gentlemen against the Players at Lord’s, he top-scored in the second innings with 64. But he wanted to do well in his finals, so ruled himself out of the 1950 Five Nations. Exams also meant little cricket, though he did take five for 78 against Cambridge.

Back home, he resumed his career with Western Province, returning to England with South Africa in 1951. He struggled on damp pitches, but hit a career-best 150 against Yorkshire at Bramall Lane, and a Test-best 83 at Headingley. There, he took his only Test wicket of the tour – Len Hutton, bowled playing for non-existent turn. That year, he was admitted to the Cape Bar, and had just established his legal practice when the squad for Australia and New Zealand in 1952-53 were selected. To his later regret, he declined the chance to be Jack Cheetham’s vice-captain.

South African cricket team on tour of England, circa May 1951. C B Van Ryneveld (Back row, first from left)

South African cricket team on tour of England, circa May 1951. C B Van Ryneveld (Back row, first from left)

Such were the demands of work that he made only three first-class appearances between the England tour and the First Test against New Zealand at Durban in December 1953, yet still topped South Africa’s series averages, with 234 runs at 46. Although he did not tour England in 1955, he was chosen for the eagerly awaited series against Peter May’s team in 1956-57. An hour before the start, at Johannesburg, Jackie McGlew withdrew with a shoulder injury, propelling van Ryneveld into the captaincy. South Africa were soundly beaten, and lost again after McGlew returned for the Second Test. By the Third, van Ryneveld was back in charge, but had already told the selectors he was soon to be married and would miss the final two matches. With McGlew ruled out, he was persuaded to change his mind, and the newly-weds ended their honeymoon early. By way of compensation, the board flew his wife to Johannesburg to watch the Fourth Test, although she could not stay in the same hotel as her husband.

The Third had been drawn, before Hugh Tayfield’s 13 wickets got South Africa back into the series at the Wanderers, where he and van Ryneveld were carried off by jubilant spectators. Then, on a shocking pitch at Port Elizabeth, against an injury-hit England, they made it 2–2. “We were lucky to draw the series,” van Ryneveld wrote later.

By the time Ian Craig’s Australians toured the following year, he had been elected to the South African parliament as an MP for the United Party, who opposed the brutal legislation of H. F. Verwoerd’s ruling National Party. Van Ryneveld’s constituency in East London was 600 miles from his home but – despite maintaining his legal practice – he declared himself available for selection. “Frankly, I hadn’t made 50 runs before the Tests started,” he said. “That’s no way to take on the Australians.” He missed the drawn First Test with a hand injury, but took charge for the next four, three of them lost heavily.

It was in the last that he withdrew Heine and Adcock, to their disgust (though Adcock later forgave him). Van Ryneveld had been influenced by seeing New Zealand’s Bert Sutcliffe hit by Adcock in 1953-54, and struck a pre-series agreement with Craig, though he later felt he could have allowed more liberal use of the short ball. He made just two more first-class appearances, almost five years later.

Van Ryneveld was one of 11 United MPs who felt the party too weak in their opposition to apartheid. They resigned en masse to form the Progressive Party, but in 1961 all but one (Helen Suzman) lost their seat at a general election, and van Ryneveld returned to the law in Cape Town. In 1962, he co-defended five black protesters charged with instigating a march that led to violent riots in Paarl. Three were sentenced to death. Van Ryneveld called the judgment “an awful indictment of the system”.

His sporting status did not prevent him falling foul of the authorities. After finding legal work elusive, he went into merchant banking. In 1970, the broadcaster Charles Fortune asked him into the commentary box at a Test match, but was swiftly told to withdraw the invitation: “We can’t have that Prog on air. Make an excuse.”

In 2012, the Newlands CEO Andre´ Odendaal began staging reunions of former players on the field during the New Year Test: van Ryneveld was among the first to hold the Western Province flag. “He was one of a few prominent figures from the old racial cricket Establishment who wasn’t dragged whingeing and complaining into the new order after unity and democracy,” said Odendaal. “He displayed integrity and his characteristic old-world gentlemanly respect and humility to the end.”