Clive Rice may have been excluded from Test cricket by South Africa’s sporting isolation, but he was still one of the world’s leading all-rounders in the late Seventies and Eighties. In 1981, he was a Wisden Cricketer of the Year.

Clive Rice’s achievements with Nottinghamshire in 1980 proved just a warm-up for 1981, when he led the county to a first Championship since 1929.

It takes a very special person to absorb the trauma of being sacked by a club and then return to lead them to their most successful season for more than 50 years. But then Clive Edward Butler Rice, born in Johannesburg on July 23, 1949, is someone special.

The 31-year-old South African arrived at Trent Bridge in 1975 – after Nottinghamshire, then under the management of Jack Bond, had switched their attentions from his fellow-countryman, Eddie Barlow – and it was three years later that they decided his aggressive and positive pursuit of success was deserving of the captaincy.

His involvement, however, with World Series Cricket, at a time when Nottinghamshire were open critics of Kerry Packer’s wheelings and dealings, led to the Trent Bridge hierarchy stripping him both of the leadership and his place on the staff before he had had the opportunity to assert himself. Following threats of protracted legal battles, between club and player, a compromise of a kind was reached with Rice maintaining his position on the books while returning the captaincy to Mike Smedley.

A season and a half later the Nottinghamshire manager, Ken Taylor, reappointed Rice as captain, a move that did not meet with total acceptance by members of the county. But, leading from the front, Rice has in a short time improved Nottinghamshire’s fortunes, for so long at a low ebb. In terms of captaincy, he had much to learn tactically, his previous experience being limited to leading out his club side, Bedford View, in South Africa, but although listening to and digesting the advice of Taylor and such senior Nottinghamshire players as Mike Harris, Rice has retained his own identity.

It is enormously to his credit that the pressures and strains of captaining the side have not detracted too much from his own statistical contribution. “I am sometimes thinking of many other things when I am out in the middle batting,” he conceded. Yet if, last season, his output was reduced by some small percentage, this was more than compensated for by the influence he had on those around him. The players, not least Derek Randall, readily acknowledge the spirit, determination and enthusiasm that spread through the dressing-room as a result of Rice’s vibrant attitude to the game.

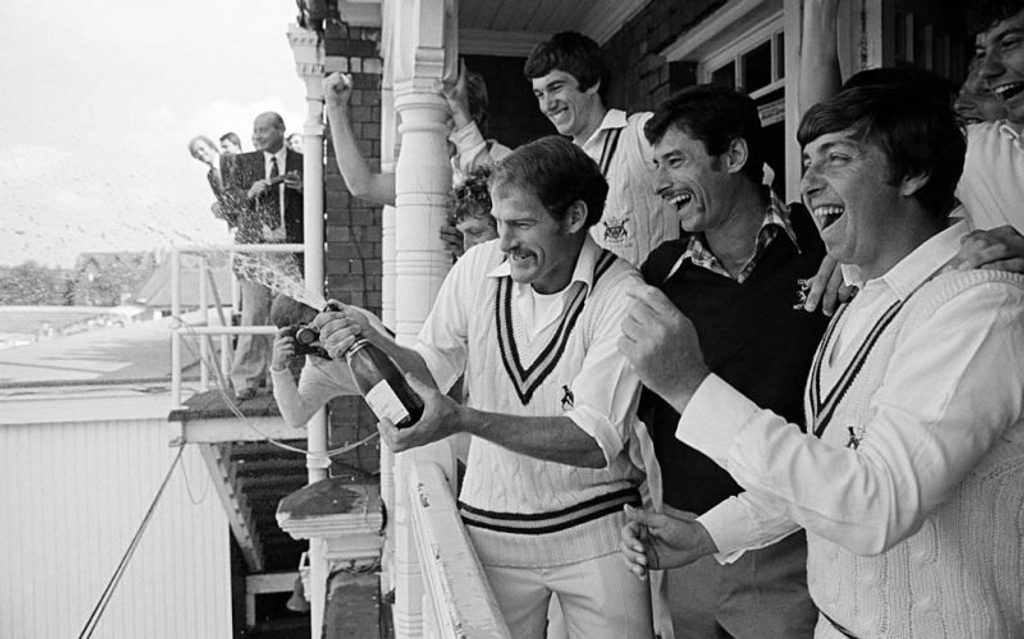

Nottinghamshire celebrates their Championship win in 1981, with Rice leading the proceedings

Nottinghamshire celebrates their Championship win in 1981, with Rice leading the proceedings

Above all else, Rice, like so many Springboks, is dedicated to winning. To coin a sporting cliche, he leads by example. Whether with the bat, the ball or in the field, he has consistently produced the kind of performances that have uplifted less-talented colleagues. Despite South Africa’s continuing absence from Test cricket – a fact which frustrates him to the point of embitterment – Rice has used the county game and South African cricket, as well as his flirtation with WSC, to reveal himself as one of the most complete and competitive of modern all-rounders.

As a right-handed bat, he has gained a reputation as a prodigious hitter. There are few more powerful front-foot drivers around, but in no way have his technique and timing been sacrificed for ferocity. At his best he is equally untroubled by pace or spin, and his ability to hit through the ball on turning pitches has often saved Nottinghamshire when at their most vulnerable.

Clive Rice in first-class cricket:

Batting average: 40.95

Bowling average: 22.49https://t.co/eevSMDcRnr— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) April 7, 2020

It is almost taken for granted at Trent Bridge now that Rice completes 1,000 first-class runs in a season. His best aggregate was in 1978 when he scored 1,871 runs at an average of 66.82. In 1980 he hit five centuries, including two, both unbeaten, in the match against Somerset, and reeled off seven fifties. His run-making has often been best illustrated in the limited-overs competitions, particularly the John Player League. In 1977 he blitzed all previous figures with a total of 814 runs on Sundays alone.

There is something of the showman in his make-up, being often at his best when a ground is full and he can respond to the sort of crowd participation upon which he would thrive if the Test door were open to him. He would almost certainly be guaranteed a place in a South African side for his batting alone, but run-making is just one facet of a multi-talented cricketer who came to prominence in his own country as much for his pace bowling as his strokeplay.

Although troubled by an assortment of injuries, he has given the Nottinghamshire attack the kind of hostility and penetration it has not had for years. At times his partnership with the New Zealander, Richard Hadlee, has all but rekindled memories of the halcyon days of Larwood and Voce. In the last three seasons they have represented, when fit together (which has been too seldom), one of the most formidable opening attacks in county cricket.

Rice is also held in high esteem in South Africa, where he returns annually in search of sun and cricketing success. In 1980 he helped Transvaal win both the Currie Cup and Datsun Shield for the second successive year, his 43-wicket haul taking him to the top of the national averages. However, the Transvaal side being so rich in talent, batting opportunities have been fewer than he would have liked. He had not, in fact, scored a first-class century in South Africa until the winter of 1979/80 when he made two, in successive matches, against Western Province and Natal. But any honours he achieves in South Africa detract in no way from his ambition to take Nottinghamshire to the top of the tree.