CB Fry, a great all-rounder in life as well as sport, died on September 7, 1956. His Wisden obituary profiled a truly extraordinary figure.

Fry, Charles Burgess died on September 7, 1956, aged 84.

Charles Burgess Fry was born into a Sussex family on April 25, 1872, at Croydon, and was known first as an England cricketer and footballer, also as a great all-round athlete who for a while held the long-jump record, a hunter and a fisher, and as an inexhaustible virtuoso at the best of all indoor games, conversation.

He was at Repton when a boy, where at cricket he joined the remarkable and enduring roll of superb young players emanating from the school – Fry, Palairet, Ford, JN Crawford, to name a few. At Oxford, he won first-class honours in Classical Moderations at Wadham, and it is a tribute to his calibre as a scholar and personal force that most of the obituary articles written after the death of Viscount Simon named Fry in a Wadham trinity with Birkenhead. Not the least doughty and idealistic of his many-sided achievements was as a Liberal candidate for Brighton, where he actually polled 20,000 votes long after he had ceased to live in Sussex and dominate the cricket field.

With all his versatility of mind and sinew, Fry himself wished that he might be remembered, as much as for anything else, by his work in command of the training-ship Mercury. For 40 years he and his wife directed the Mercury at Hamble, educating youth with a classical sense of values. He once invited the present writer to visit Hamble and see his boys play cricket and perform extracts from Parsifal! Hitler sent for him for advice during the building-up of the Youth Movement in Germany. He was a deputy for the Indian delegation to the first, third, and fourth Assemblies of the League of Nations, edited his own monthly magazine more than half a century ago, and was indeed a pioneer in the school of intelligent and analytical criticism of sport.

He wrote several books, including an autobiography, and a Key Book to the League of Nations, and one called Batsmanship, which might conceivably have come from the pen of Aristotle had Aristotle lived nowadays and played cricket.

Fry must be counted among the most fully developed and representative Englishmen of his period; and the question arises whether, had fortune allowed him to concentrate on the things of the mind, not distracted by the lure of cricket, a lure intensified by his increasing mastery over the game, he would not have reached a high altitude in politics or critical literature. But he belonged – and it was his glory – to an age not obsessed by specialism; he was one of the last of the English tradition of the amateur, the connoisseur, and, in the most delightful sense of the word, the dilettante.

As a batsman, of course, he was thoroughly grounded in first principles. He added to his stature, in fact, by taking much thought. As a youth he did not use a bat with much natural freedom, and even in his period of pomp he was never playing as handsomely as his magnificent physical appearance seemed to suggest and deserve. He was, of course, seen often in contrast with Ranjitsinhji, who would have made all batsmen of the present day, Hutton included, look like so many plebeians toiling under the sun.

Yet, in his prime, Fry was a noble straight-driver. He once said to me: “I had only one stroke maybe; but it went to ten different parts of the field.” But in 1905, when the Australians decided that Fry could make runs only in front of the wicket, mainly to the on, and set the field for him accordingly, he scored 144 in an innings sparkling with cuts.

In his career as a cricketer, he scored some 30,000 runs, averaging 50, in an era of natural wickets, mainly against bowlers of great speed or of varied and subtle spin and accuracy. From Yorkshire bowling alone he scored nearly 2,500 runs in all his matches against the county during its most powerful days, averaging 70, in the teeth of the attack of Hirst, Rhodes, Haigh, Wainwright, and, occasionally, F. S. Jackson. In 1903 he made 234 against Yorkshire at Bradford. Next summer he made 177 against Yorkshire at Sheffield, and 229 at Brighton, in successive innings

Ranjitsinhji’s performances against Yorkshire were almost as remarkable as Fry’s; for he scored well over 1,500 runs against them, averaging more than 60 an innings. In 1901 Fry scored six centuries in six consecutive innings, an achievement equalled by Bradman, but on Australian wickets and spread over a season. Fry’s six hundreds, two of them on bowler’s wickets, came one on top of the other within little more than a fortnight.

Jack Hobbs, Sir Donald Bradman and CB Fry at the Grosvenor House Hotel in London, 1948

Jack Hobbs, Sir Donald Bradman and CB Fry at the Grosvenor House Hotel in London, 1948

The conjunction at the creases of CB Fry and KS Ranjitsinhji was a sight and an appeal to the imagination not likely ever to be repeated; Fry, 19th century rationalist, batting according to first principles with a sort of moral grandeur, observing patience and abstinence. At the other end of the wicket, Ranji turned a cricket bat into a wand of conjuration. Fry was of the Occident, Ranji told of the Orient.

Cricket can scarcely hope again to witness two styles as fascinatingly contrasted and as racially representative as Fry’s and Ranjitsinhji’s. Between them they evolved a doctrine that caused a fundamental change in the tactics of batsmanship. Play back or drive. Watch the ball well, then make a stroke at the ball itself and not at a point in space where you hope the ball will presently be. At the time that Fry was making a name in cricket most batsmen played forward almost automatically on good fast pitches, frequently lunging out at full stretch. If a ball can be reached only by excessive elongation of arms and body, obviously the pitch of it has been badly gauged. Fry and Ranjitsinhji, following after Arthur Shrewsbury, developed mobile footwork.

It is a pungent comment on the strength of the reserves of English cricket half a century ago that Fry and Ranji were both dropped from the England team at the height of their fame. In 1901 Fry scored 3,147 runs, average 78.67; in 1903 he scored 2,683 runs, average 81.30. In 1900 Ranjitsinhji scored 3,065, average 87.57. Yet because of one or two lapses in 1902, both these great players were asked to stand down and give way to other aspirants to Test cricket.

As we consider Fry’s enormous aggregates of runs summer by summer, we should not forget that he took part, during all the extent of his career, in only one Test match lasting more than three days, and that he never visited Australia as a cricketer. For one reason and another Fry appeared not more than 18 times against Australia in 43 Test matches played between 1899, when he began the England innings with WG Grace, and 1912, in which wet season he was England’s captain against Australia and South Africa in the ill-fated triangular tournament.

By that time, he had severed his illustrious connection with Sussex and was opening the innings for Hampshire. The general notion is that Fry was not successful as an England batsman; and it is true that in Test matches he did not remain on his habitual peaks. None the less, his batting average for Test cricket is much the same as that of Victor Trumper, MA Noble, and JT Tyldesley. The currency had not been debased yet.

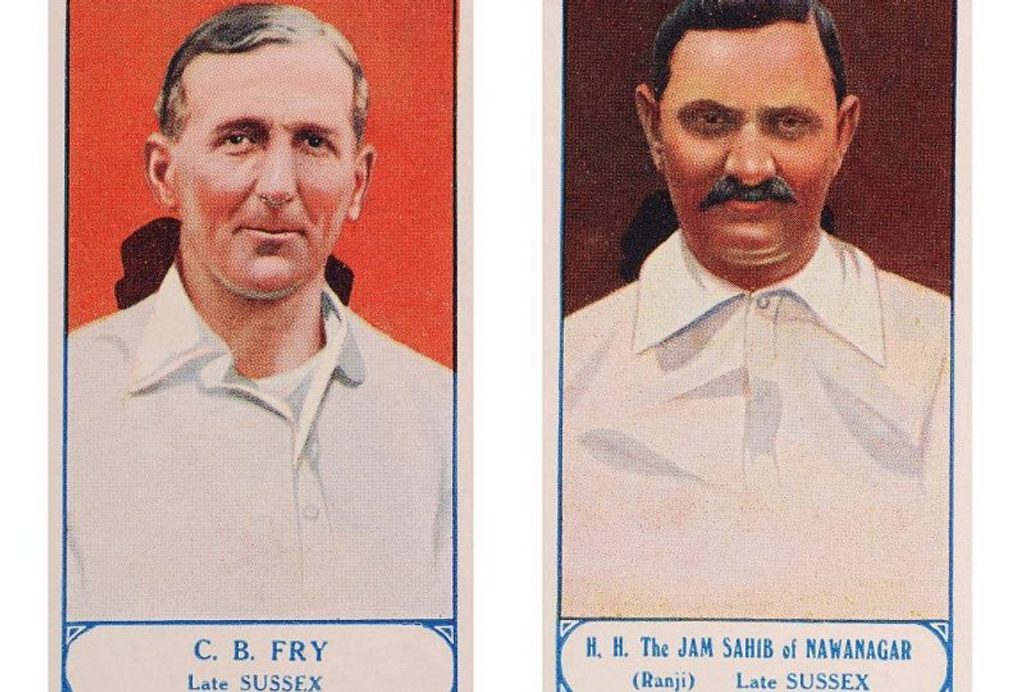

Vintage cigarette cards featuring CB Fry and The Jam Sahib of Nawangar, KS Ranjitsinhji of Sussex County Cricket Club

Vintage cigarette cards featuring CB Fry and The Jam Sahib of Nawangar, KS Ranjitsinhji of Sussex County Cricket Club

Until he was no-balled for throwing by Phillips – who also called Mold at Old Trafford – Fry was a good fast bowler who took six wickets for 78 in the University match, opened the Gentlemen’s bowling against the Players at The Oval, and took five wickets. Twice he performed the hat-trick at Lord’s. He played Association football for his university, for the Corinthians, Southampton, and for England.

In his retirement he changed his methods as a writer on cricket and indulged a brisk impressionistic columnist style, to suit the running commentary needed by an evening paper: “Ah, here comes the Don. Walking slowly to the wicket. Deliberately. Menacingly. I don’t like the look of him. He has begun with a savage hook. He is evidently in form. Dangerously so. Ah, but he is out…”

Essentially he was an analyst by mind, if rather at the mercy of an impulsive, highly strung temperament. He sometimes, in his heyday, got on the wrong side of the crowd by his complete absorption in himself, which was mistaken for posing or egoism. He would stand classically poised after making an on-drive, contemplating the direction and grandeur of it. The cricket field has seen no sight more Grecian than the one presented by CB Fry in the pride and handsomeness of his young manhood.

After he had passed his 70th birthday, he one day entered his club, saw his friend Denzil Batchelor, and said he had done most things but was now sighing for a new world to conquer, and proposed to interest himself in racing, attach himself to a stable, and then set up on his own. And Batchelor summed up his genius in a flash of wit: “What as, Charles? Trainer, jockey, or horse?”

It is remarkable that he was not knighted for his services to cricket, and that no honours came his way for the sterling, devoted work he did with the training-ship Mercury.