Bob Willis was one of England’s greatest fast bowlers. But his success came only after several years of battles with injury, as Wisden recorded in naming him a Cricketer of the Year in 1978.

This tribute was written in the 1977 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack. Willis took 325 wickets in 90 Test matches, with his greatest triumph coming in the Headingley Test in the 1981 Ashes series, where he claimed 8-43.

READ MORE ALMANACK TRIBUTES

If Geoff Boycott’s timely return made all the difference to the batting, the new-ball fire power of Bob Willis, which yielded 27 wickets, was of special significance in England’s high summer of success. No England bowler of authentic speed can boast a comparable record in a home series against Australia – indeed only Jim Laker (46) and Alec Bedser (39) of different styles have done better – and, fittingly, in the final euphoric moments at Headingley when the Ashes were recaptured Willis took his 100th Test wicket.

It was singularly appropriate that team and personal triumph should go hand in hand, for few players have given such loyal and unstinted service to England as the wholehearted Willis. And he has had more than his fair share of the other side of fortune. As late as May, 1975, his career was imperilled by major operations to both knees, and while in hospital he suffered a blood clot and spent several unpleasant hours. Until the middle of that season he was on crutches.

In Willis’ own words the operations were similar to a 50,000-mile service, but his comeback would not have been complete without his own determination and a fortuitous meeting with Dr Arthur Jackson, an Australian disciple of the German Van Aaken’s theory of the value of slow long-distance running to build stamina. Willis first met Dr Jackson during the 1974/75 tour of Australia, and formed a close friendship which has continued with phone and letter exchanges.

Bob Willis of Surrey carries the drinks tray at Trent Bridge, July 3, 1970

Bob Willis of Surrey carries the drinks tray at Trent Bridge, July 3, 1970

Pain and worry became Willis’ constant companions around that period. From the first match in Australia he had knee trouble, and only drugs kept him going. He had ten injections before the inevitable breakdown, and he was flown home before the start of the last Test. Back at Edgbaston, he went down again in the first Benson and Hedges Cup game and he knew there was no alternative to surgery.

After the operations there was the drudgery of daily exercises. Fast bowling is essentially a matter of rhythm and co-ordination, and the idle weeks produced a crop of niggling complaints like strained stomach muscles and bruised heels. Another restricted season meant a chance to play in only the last two Tests against the West Indies, though he managed 5-42 in the second innings and eight wickets in all at Headingley.

The glamour faded when he joined the dole queue in the following winter. There had been an offer to coach in South Africa, but understandably Willis did not want to risk playing too soon on hard surfaces. The slow, cruel grind back to fitness and form had its turning point in India, traditionally anything but a bountiful hunting ground for English fast bowlers, in 1976/77.

Wisely Alec Bedser and his selectors opted for a speed attack led by Willis, and with equal prudence Tony Greig, the captain, and Ken Barrington, the manager, urged Willis to abandon his somewhat circular tour to the wicket in favour of a simple and direct approach. Well-formed habits are not easy to eradicate, but it was characteristic of the man that from the moment the team arrived at Bombay Willis marked out his longest run and assiduously applied himself to his new task. He succeeded.

England bowler Bob Willis appeals unsuccessfully against Viv Richards, August 1976

England bowler Bob Willis appeals unsuccessfully against Viv Richards, August 1976

On pitches prepared for spinners Robert George Dylan Willis – he added Dylan to his given names after falling under the spell of the American folk rock singer at the age of 12 – was often too much for India’s batsmen. He took 20 Test wickets, including 5-27, which put England firmly on the path of victory in the second match at Calcutta.

Since then Willis has had 6-53 at Bangalore, 7-78 at Lord’s, 5-88 at Trent Bridge and 5-102 at The Oval, and has put to flight any who doubted his right to be acclaimed as one of the world’s foremost fast bowlers.

Nevertheless the strain of India and the stamina-sapping heat of Sri Lanka took its toll and Willis ran out of steam in the Melbourne Centenary Test. It was understandable as England had been asked to complete an almost impossible itinerary. The sequel was another visit to Dr Jackson at Sydney, and his advice to run five miles a day was faithfully carried out. Also Willis has been obliged to spend more time than he would have wished as a patient at the Edgbaston clinic of Bernard Thomas, who accompanies MCC and Warwickshire as a trusted physiotherapist.

***

Perhaps it was pre-ordained that the amiable Willis should not have an easy climb to the top. In his first trial at The Oval he was turned down, and later, even though he had played in an Ashes-winning side in Australia, he had to leave Surrey to get a county cap with Warwickshire.

All his early cricket was with Surrey clubs and schools, and nothing seemed more natural than he should spend his career at The Oval. The family had moved from Sunderland, where he was born on May 30, 1949, to Stoke d’Abernon, near Guildford, when he was six. Father, now retired, was a sub-editor with the BBC, and Bob, who has an elder brother and sister, went to the Royal Grammar School, Guildford. When he played cricket in the back garden with his brother David (a notable wicketkeeper-batsman with Blackheath) he always pretended to be either John Snow or Brian Statham.

Soon, in 1970/71, he was to be bowling alongside Snow, having been sent to Australia to join Illingworth’s party as a replacement for the injured Ward.

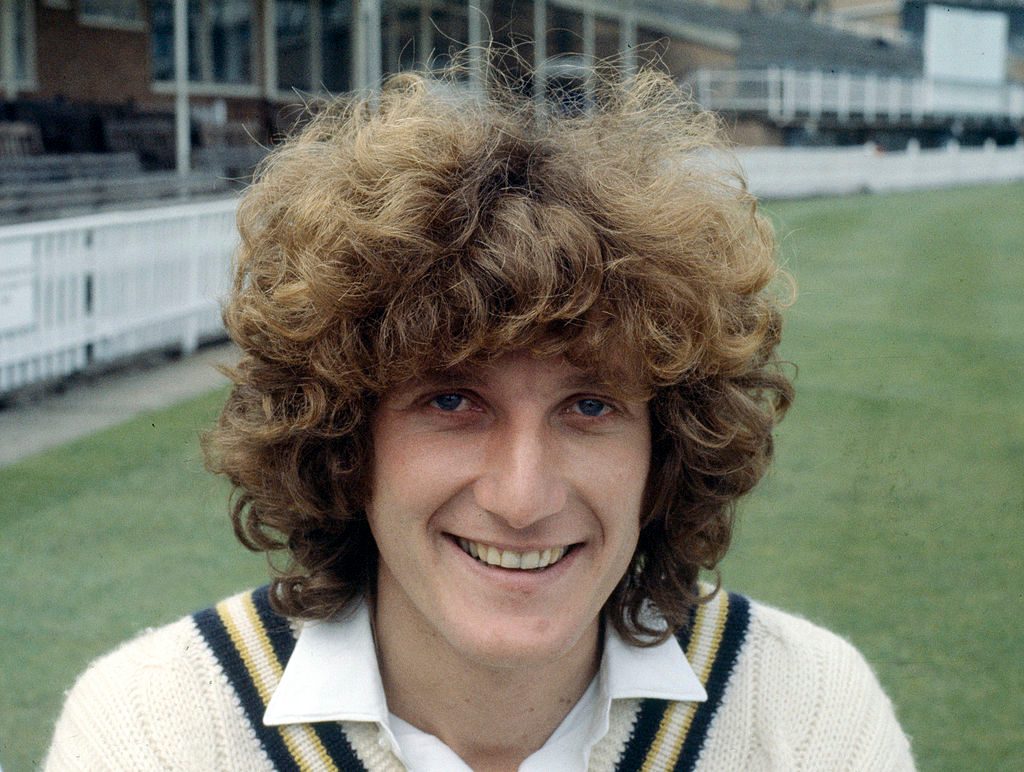

Bob Willis would ultimately play in 90 Test matches between 1971 and 1984

Bob Willis would ultimately play in 90 Test matches between 1971 and 1984

The urge to bowl fast was always with him. It came naturally, and his potential was quickly recognised by selection for Surrey Schools – at that stage Watcyn Evans was his invaluable mentor – and Surrey Colts. In 1968/69 he went to Pakistan with Middlesex and Surrey Young Cricketers, and his initiation into first-class county cricket came in August, 1969, when, given a season’s trial by Surrey, he squeezed in five matches. He took 17 wickets at 19.35 each, and topped the county bowling averages.

Surrey, however, already had established pace bowlers in Arnold and Jackman, and Willis was in the unsatisfactory position of being in and out of the side. At the end of the 1970 summer Willis prepared for a winter’s work at the Crystal Palace Recreation Centre, and the Saturday occupation of keeping goal for Corinthian Casuals – he also had a spell with Guildford City. One morning out of the blue came a call from Lord’s with an urgent summons to fly out to Australia. As the tour leaders Illingworth and his vice-captain Cowdrey had barely seen him bowl more than a few overs Willis believes he owed his recommendation to John Edrich, his Surrey team-mate and one of the senior members of the MCC party.

Edrich proved to be a sage judge, for Willis won his way into the last four Tests, took 12 wickets and several crucial catches, and his infectious enthusiasm and team spirit played no small part in Australia’s downfall. It was, as Willis says, fairytale stuff, particularly as another Test followed in New Zealand. But the purple suddenly took on a black edge, and by the month of July, 1971, the new bowling star of England had decided to break with Surrey. After being twelfth man for the first Test, Willis was not in Surrey’s side for the next match.

Bob Willis stands behind Muhammad Ali, who’s in discussion with Warwickshire players

Bob Willis stands behind Muhammad Ali, who’s in discussion with Warwickshire players

Jackman had settled in the team, and when he returned from Australia Willis was offered terms he felt he could not accept. There was but one escape from his situation, and that was to leave The Oval. Surrey tried to persuade him to stay, but Willis was adamant, and a difficult period in his career ended with his joining Warwickshire to the disappointment of Leicestershire and Lancashire. Willis was banned from playing in the championship until July, but he was more than consoled by helping his new county to the title. In the last home match he took 8-44, winding up Derbyshire’s first innings with a hat-trick, and was awarded his county cap.

He did not make the party to India and Pakistan in that winter. Instead he coached at Pretoria, and also joined a private tour of South Africa. In 1973 he was again troubled by a series of minor complaints, but he returned for the final Test against the West Indies at Lord’s, and in a total of 652-eight declared, returned the respectable figures of 4-118.

Selection for the tour of the West Indies was automatic, but he did not bowl well, partly because of a mistaken policy to reserve him for the Tests. Back home he played in the first Test against Pakistan at Old Trafford and the last at the Oval. In between he had a recurring back injury, and ahead was the trauma of the operations to be followed by the stern discipline of the slog of the build up with weights in a gymnasium and the daily jog around deserted fields.

England captain Bob Willis is presented with the series trophy,1983

England captain Bob Willis is presented with the series trophy,1983

Happily determination is one virtue Willis does not lack, and his re-emergence as a top ranking fast bowler was well and truly deserved. As part of his trade he is properly belligerent if the need is there, and, in good and bad times, he is a marvellous tourist, always at the heart of the fun and the fight. With his 6ft 6ins frame topped by a thatch of unruly hair Bob Willis is a big man in every sense. And he had the good sense to turn down an invitation to join the Packer circus.