Bob Willis passed away on Wednesday, December 4th, aged 70. When he announced his retirement in 1984, Bob Willis had carried the burden of sole spearhead of England attack for years. In the 1985 Wisden Almanack, David Frith put his career in context.

First published in the 1985 Wisden Almanack.

Richardson had Lockwood; Larwood had Voce; Trueman had Statham; but Willis was almost alone. Just how much of an extra force for England Willis might have been, given a regular complementary strike bowler, is a question which will hang suspended in time. True, he linked with Botham for several series, and believed in his partner implicitly – until the final phase, by which time Botham had lost his thrust and Willis himself, still valiantly withstanding the hardships of ageing frame and suspect knees, sensed that the sand in his own hour-glass was nearly all in the bottom.

For one who is often outrageously convivial in a social setting, Bob Willis could be surprisingly, even shockingly, solitary when in cricket battledress. The young man flown to Australia in emergency during Illingworth’s 1970/71 tour bent himself into predatory shape in the gully and held some spectacular catches; but Willis the Elder, a dozen years on, unlikely captain of England, struck a memorable and almost perpetual pose in the isolation of mid-off, thin arm across concave chest, large hand propping that promontory of a chin, blue-grey eyes seemingly glazed against what became, in 1982/83 and 1983/84, a painful scene as England’s mediocre bowling was exposed by the batsmen of Australia and New Zealand.

Bob Willis appealing unsuccessfully for the wicket of Viv Richards in 1976.

Bob Willis appealing unsuccessfully for the wicket of Viv Richards in 1976.

It was as well to remember, at times of exasperation at his detached air, that he merely accepted the highest honour of the England captaincy; he didn’t demand it. The selectors had boxed themselves in by dropping Fletcher.

Often Willis tried to do it alone, and that was when his lone role and his uniqueness among English pace bowlers were so gallingly obvious. Inevitably in 1984, with the defeats piling up and his own condition and future in doubt, he was relieved of the captaincy. He graciously returned to the ranks and played out his last few Tests under Gower. When his bowling was hammered by the West Indians – Holding in particular – there were still those who wished to believe that it was luck on the batsmen’s part, and that Willis remained a force. We were, in fact, watching the death throes of a great fast-bowling career.

Only Bob Willis’s height ever encouraged any sort of belief that he would become an international fast bowler. His run-up was intimidating but slightly absurd. Even he appreciated this, especially after seeing Gooch imitate it, a fateful observation late in life which persuaded him to bring his right arm forward instead of pumping it across his rump like a frenzied jockey in the home straight. Yet irrespective of the low marks for aesthetic quality in his action, that long right arm, which came down and across at such an unlikely angle, propelled the ball at a hot pace, with steep bounce and unusually threatening movement in towards the batsman.

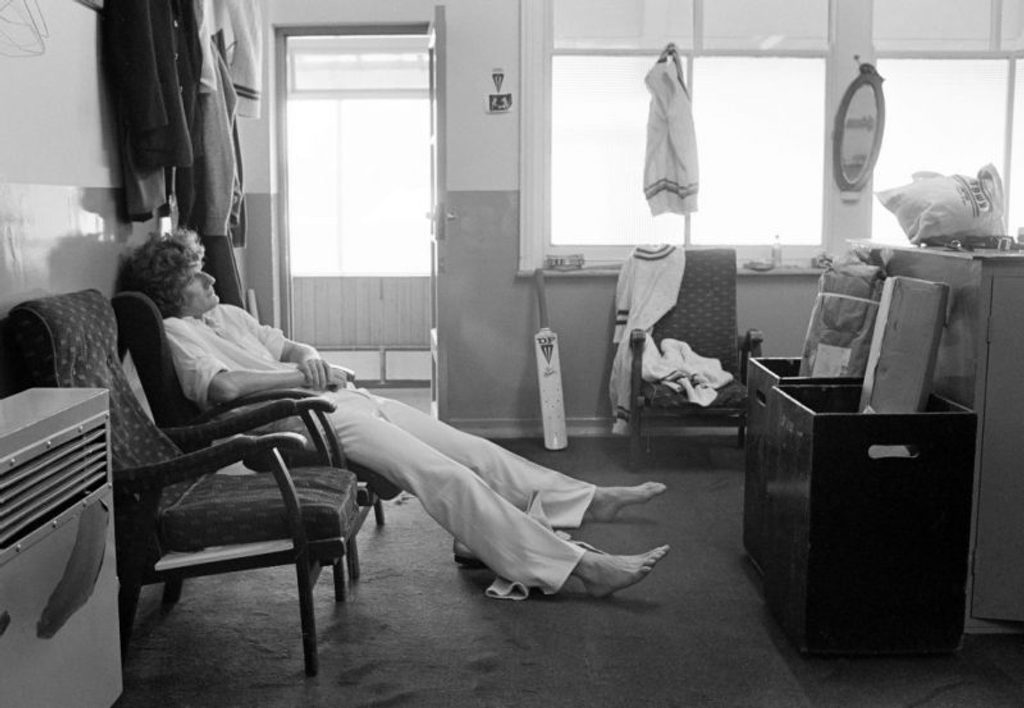

Bob Willis relaxing in the dressing room after a day in the field with Warwickshire

Bob Willis relaxing in the dressing room after a day in the field with Warwickshire

Sometimes that batsman, as in McCosker’s case at Melbourne during the Centenary Test, was pinned by it. McCosker’s jaw was broken, and Willis was booed as he left the ground, in blazer and flannels, and strode up through the park towards the team’s hotel. Anyone getting in his way that evening would have been squashed flat.

A year later one of his bouncers hit Pakistan’s nightwatchman, Iqbal Qasim, a fearful blow in the mouth. Again, there was no outward show of regret, and this time his captain, Brearley, supported his tactics in bowling short.

The fast bowlers’ union went into liquidation around the time that all sorts of other honourable institutions and codes were developing cracks, and Willis the tail-end batsman was as much in need of a helmet, when they came into vogue, as any opening batsman – in fact, more so. Yet he still managed to appropriate a whimsical record: most not outs in Test cricket. If he looked ungainly as he rattled in to bowl, he seemed even more of an oddity as he defied the bowling, with helmet perched on his thick mass of hair, left leg thrust down the pitch, and that curtain-rail probe with the bat – a cross-pitch slice which somehow made contact.

He once hit Australian fast bowler Alan Hurst for six over cover point at Adelaide. But his finest hour with the bat was a 171-minute innings of 24 not out at The Oval in 1980, when he saw Willey to his century, shared in an extraordinary unbeaten tenth-wicket stand of 117 after England had been 92 for nine in their second innings, and held out against the sudden prospect of a West Indian victory.

***

Robert George Dylan Willis was awarded the MBE for services to cricket, an expression interpreted by the majority as standing for loyalty (he resisted the blandishments of World Series Cricket in 1977), patriotism (richly apparent in everything he did or said), and a displayed sense of propriety (as symbolised in his admonishment of Jackman, who had gestured to an outgoing batsman).

Those tortured, pumping knees carried him in the end of 325 Test wickets, 128 of them in 35 Tests against Australia. At the time of his retirement both were records for England. That gratified the man who, as a boy, idolised Statham and dreamed, like millions before and since, of becoming one of the rare few to play cricket for his country. And yet, in the anticlimax of his withdrawal from big cricket, as illness shortened his last season and prevented him from taking on orchestrated final public bow, he privately spoke of never treading on a cricket field again. Such was his exhaustion and disenchantment.

If he was no outstanding tactical genius as captain, he could be an effective motivator. He particularly showed this quality as senior pro, chiefly in the dressing-room. But towards the end his feelings bordered on disgust at the conviction that some of England’s cricketers accepted failure too readily. Nor was he able to close himself off against media comment. His finest hour was at Headingley in 1981, when his eight for 43 further stunned an Australian side already dazed by Botham’s awesome 149 not out in England’s follow-on innings.

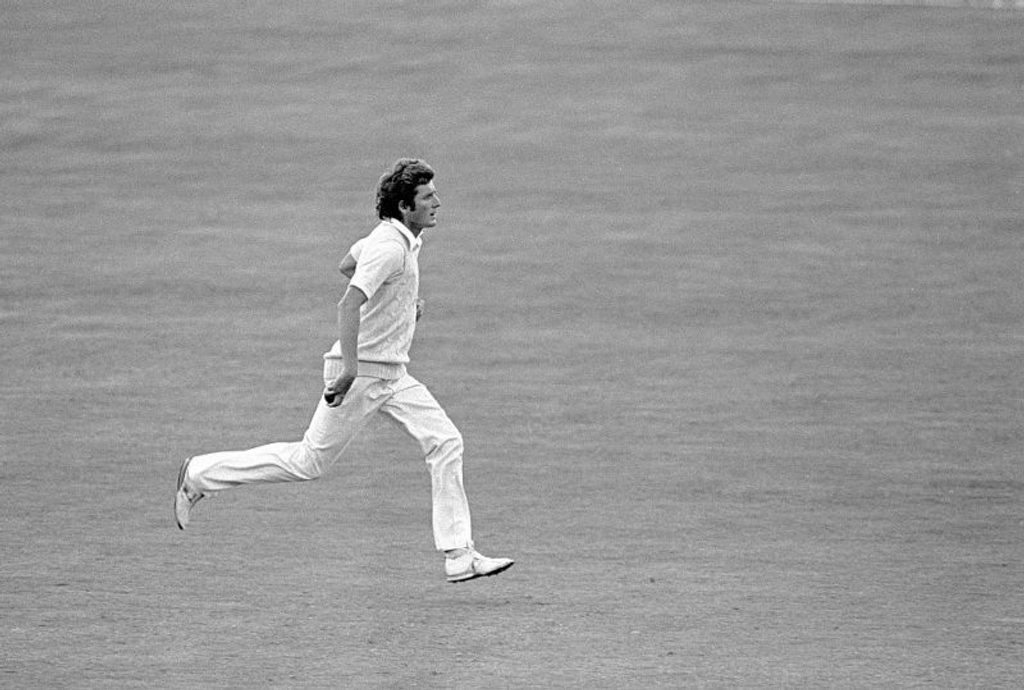

Bob Willis running into bowl for England at Lord’s in 1980

Bob Willis running into bowl for England at Lord’s in 1980

In the moment of supreme exhilaration Willis was less inclined to discuss the great victory with his national television interviewer than to lambast the press – not, mark you, the relevant section of it – for earlier derogatory comments. It was only much later that the full significance of his bowling feat sank in, so wound up had he been.

Over the years he resorted to hypnotherapy to relieve his inherent tension and improve his mental and physical tuning. This helps to explain the intensity of his approach: the glaring eyes, the tight lips, taut cheeks. It might even explain his oversight in the Test at Edgbaston in 1982 when he marched out, padded, helmeted and gloved, but without his bat.

He was not always quite a universal favourite at Edgbaston. Many Warwickshire supporters were resentful because he seemed to be giving more to his country than his county. But this is less of an indictment when one reflects that after John Snow’s decline (he and Willis played in no more than five Test matches together) there was no English bowler for years, in the whole of the country, who came close to Willis for speed. He was the pronounced cutting edge – between bouts of reblading in the skilled hands of knee surgeons.

Bob Willis running off the Headingley outfield after taking the final Australian wicket in England’s famous victory there in 1981

Bob Willis running off the Headingley outfield after taking the final Australian wicket in England’s famous victory there in 1981

When, as almost an unknown, he was flown to Australia in 1970 as a replacement for Alan Ward, he was on Surrey’s books. When a county cap to place alongside his England cap (never actually worn into action, incidentally) was not forthcoming, he took himself off to Warwickshire. Having helped Surrey to win the 1971 County Championship, he underlined his value to his new county without delay, taking 25 wickets in his nine Championship matches after seeing out a half-season ban for the abruptness of his move. He rounded off Warwickshire’s own Championship triumph in 1972 with eight for 44 against Derbyshire in the last match, securing the first of his two first-class hat-tricks.

In the 12 seasons since then, some of them curtailed by injury and most by absences on England duty, Willis took 285 Championship wickets for his county at an average of 25.51. Clearly, with 325 Test wickets at 25.20 he takes his place in the Hall of Fame as an England bowler of immense stature, but with relatively scant county achievement to go with it. Had he stayed on for longer spells for his county, though, he almost certainly would have faded several years ago.

There was something tantalising about seeing Willis and Snow in tandem for Warwickshire when the Sussex bowler, then 38, was induced to come out of retirement in 1980 and helped his new county to win the John Player League. How different might the shape of England’s Test cricket have been with those two operating with the new ball throughout the 1970s? Now both are gone, Willis with his marathon run-up and too tightly contained emotions, his bent for the zany monologue and his flat, resounding laughter. The stage is empty, and all England awaits another courageous man of speed. Preferably a pair.