One remarkable performance at The Oval in 1967 elevated Asif Iqbal to hero status and earned him a Wisden Cricketer of the Year award.

Asif Iqbal went on to become one of Pakistan’s greatest all-rounders, scoring 3,575 runs at 38.85, and taking 53 wickets at 28.33 in 58 matches. He also became a key figure in Kent’s successful teams of the early 1970s.

Asif Rasui Iqbal of Pakistan is loose-limbed, athletic, of medium height and has a permanent air of restless energy. Proud, dark and intelligent eyes – he is a graduate in history and economics – miss nothing. To look at him is to sense the unusual – an eager man of deeds and action.

Many fine words and phrases were used in praise of his innings against England at The Oval – that amalgam of pure batting genius and joyous cheek – but it needs his own simple explanation to uncover his character and philosophy.

“I was annoyed,” he says. “Annoyed because I heard that a 20-over exhibition was being arranged to compensate the crowd for the early ending of the Test. Everyone seemed to accept that it was already over. I certainly didn’t. I wanted my team to be spared from taking part in an exhibition. The whole situation made me all the more anxious and determined to succeed.”

The facts ought to have daunted even Asif, who is fast becoming a specialist in the impossible. When he went in to bat at 12.20 on a late summer morning with the ball darting and swinging in the dewy atmosphere, Pakistan were 53 for seven, and about to be beaten by an innings and a considerable margin of runs.

If any team’s head was on the block awaiting the axe it was Pakistan’s. Soon it was 65 for eight. The next three hours and ten minutes scarcely belonged to reality and certainly not to setting of a modern Test. But they are now a shining page in cricket’s history.

Asif made 146, the highest score by a No.9 in a Test match, and with Intikhab Alam as his partner, 190 unbelievable runs were taken for the ninth wicket – another world record. (It might be a consoling thought for the bowlers of England that the same pair scored 100 in 38 minutes against Queensland at Brisbane in November, 1964.)

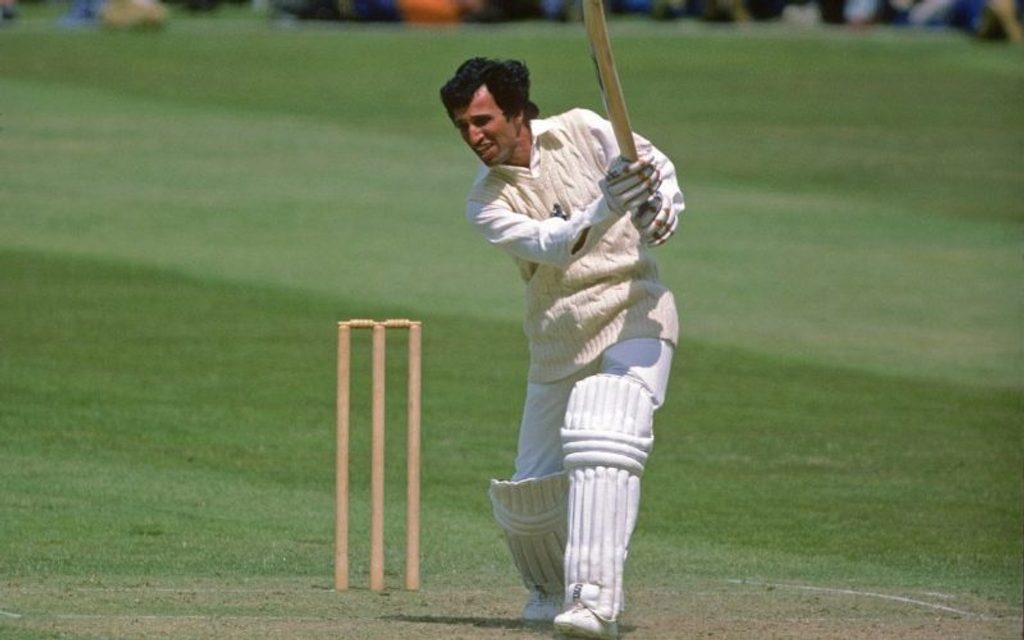

Asif Iqbal in action during the 1975 World Cup

Asif Iqbal in action during the 1975 World Cup

Pakistan, it is true, still lost, but not by an innings, for Asif, though now with an ankle injury, dismissed Cowdrey and Close and had Amiss missed before England scrambled gratefully home by eight wickets. The stigma and sting of victory were engulfed in a wave of excitement and admiration.

Yet cricket ought to have been prepared for something astonishing from Asif. Indeed his whole career seems to have been a rehearsal for the grand performance at The Oval. There was his 117 when he captained Pakistan Under-25 against MCC Under-25 at Dacca when his side was in considerable difficulty. This was his maiden century, and it is hard to believe that the other at The Oval was only his second in first-class cricket.

When he went out to bat at Dhaka, he told Maqsood Ahmed, a national coach: “Leave it to me.” He did, and with the same methods he used to crush the full England attack. He sailed into the bowling with ruthless efficiency and abandon.

Indeed something happens to Asif at the worst moments for Pakistan. Bugles sound, he mounts his own emotional charger with the reckless magnificence of a cavalry officer of old. It is not in his nature to resist a challenge. To do so would be scorned as nothing short of personal treason, the more so if attack was not met by counter-attack.

There was, too, the Test with New Zealand at Wellington in January, 1965. Pakistan’s official Cricket Annual records what is a microcosm of Asif’s career in these matter-of-fact lines: “John Reid (New Zealand’s captain) declared leaving Pakistan 188 minutes to get 259 runs to win. Pakistan’s batsmen gave another poor display. Half the side went for 17 runs, but then Asif, batting boldly, hit 52 not out in 81 minutes with eight 4’s to save his side from a crushing defeat.”

Note the simple words “batting boldly” and ponder how many batsmen would similarly react with the total at 17 for five.

“Here is a picture to quicken the blood.”

One from the archives – Jon Hotten chose an iconic picture from the International Batsman of the Year Contest as part of the My Favourite Photo series.https://t.co/GvV4PsBy9u

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) May 10, 2020

“I just don’t believe in sitting there and never striking the ball,” Asif declares. “That sort of game never produces results. You can’t go to the crease believing you can’t strike the ball. I believe firmly in the basic principles of the game. The batsman has a bat; the bowler a ball. When I am batting I want to score runs. When I am bowling I want to take wickets. This is how I approach the game. I have never cared a jot about averages, and I try and remember always that I am playing for a team, and not for myself.

“At The Oval my one concern was to make England bat again. I kept urging my partner, Intikhab, to get more and more, and it never occurred to either of us to defend. What point is there in defending in such circumstances? My whole philosophy is to attack.”

Asif’s impact on the first Test with England at Lord’s was also considerable. His medium to fast bowling on a damp pitch on the second morning stopped England from amassing a huge total, and later when he joined Hanif at 139 for seven Pakistan were in danger of following on. They took the total to 269, Asif scoring 76, and if on this occasion he played second fiddle to his captian, his innings was none the less valuable. In fact Asif was twice instrumental in changing the course and pattern of a Test, which Pakistan honourably drew.

Asif’s bowling reflects in many ways his own lively nature. It is tenacious and skilled. He learned a lot in England in 1963 as a member of the experience-seeking Eaglets, including the art of swinging the ball either way.

Asif Iqbal aggregated 23,329 runs and took 291 wickets in 440 first-class games

Asif Iqbal aggregated 23,329 runs and took 291 wickets in 440 first-class games

He has always been an apt pupil and something of a prodigy. He clearly inherited his talent from his father, Majeed Razui, who played for Hyderabad. Unhappily, he died when Asif, who was born at Hyderabad (India) on June 6, 1943, was only six months old, but there were four uncles to advise and encourage. Rauf, Yousaf and Rahim represented a specialist batsman and bowler and all-round cricket, and the fourth, Ghulam Ahmed, the noted Indian Test off-break bowler, was a source of great influence.

Thus from the first Asif had wise and experienced counsel. At only nine years of age he made the Aliya School team, and even at Nizam College, Hyderabad, he had two seasons for Hyderabad in the Ranji Trophy, India’s leading competition. In 1961 he was chosen for the South Zone against the touring Pakistanis, captained by Fazal Mahmood, and playing as A.I. Rizvi made his presence felt with a match record of six wickets, including four for 52 in the first innings.

The same year, like so many of the Islamic faith, Asif moved to Karachi, Pakistan, joining his brother Dr Shahid Iqbal, a well-known University cricketer. There is now a family engineering concern in Karachi, in which Asif serves on the administrative side.

Also in 1961, Asif played for the Governor’s XI against E.R. Dexter’s MCC side, but the newly-laid Lyallpur pitch was too uncertain to help create individual reputations. In fact the most notable fact of a low-scoring match was that Hanif collected a pair. Asif was now launched on a representative career in his new colours. In England he was the Eaglets’ leading wicket-taker, and an almost equally successfully batsman.

Back home his talent was carefully nursed and nourished. He took part in three unofficial Tests with a visiting Commonwealth side, and there was further experience in tours to Ceylon and East Africa. In two matches in Kenya he took 20 wickets.

Asif Iqbal was instrumental in Kent’s glorious surge during the Seventies

Asif Iqbal was instrumental in Kent’s glorious surge during the Seventies

By now his apprenticeship was complete. He was conditioned for his first Test in 1964 at Karachi against Australia. He had a satisfactory debut. Batting at No.9 he scored 41 and 36, and bowled Bob Cowper and Johnny Martin.

Selection for Pakistan’s visit to Australia and New Zealand in the same year was automatic. He played in all four Tests with encouraging results, but never, he stresses, did he find it necessary to change the methods he had used all along. He took 33 wickets, the highest number on the tour, including 18 at 13.77 in the Tests with New Zealand and two more in the only Test against Australia at Melbourne.

In the return series with New Zealand, bowling successes were understandably more difficult to come by on Pakistan’s slower pitches, but he managed four wickets in the Third Test, a performance supported by scores of 51 and 40 in other Tests.

Asif’s appointment as captain of Pakistan’s under-25 side early in 1967 was not only popular and well-merited, but carried a strong pointer to the future. Clearly he was being groomed for higher responsibilities.

As a leader he lost none of his individual freshness, panache and enthusiasm. His players responded to his uncomplicated approach with enthusiasm.

MCC’s visiting players were often astonished at the speed of Asif’s running between the wickets, and, it must be confessed, so too were his own partners, who toiled by as much as the length of the pitch on one interesting occasion! For all that excess of zeal, it was a spirit which uplifted Pakistan’s cricket.

Understandably Asif’s many-sided talents made him the target of several counties as soon as overseas players were permitted in the Championship on immediate registration. Asif chose Kent – to their undisguised gratification.